Editor’s note: Following is the second part of a story series by contributing writer Brent Engel.

Joseph Folk had a legitimate claim to Missouri’s 1912 Democrat presidential nomination.

At least, he and many others thought so.

Two years earlier, the party had named the former governor as its choice. His progressive policies aligned with those of three-time failed presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan.

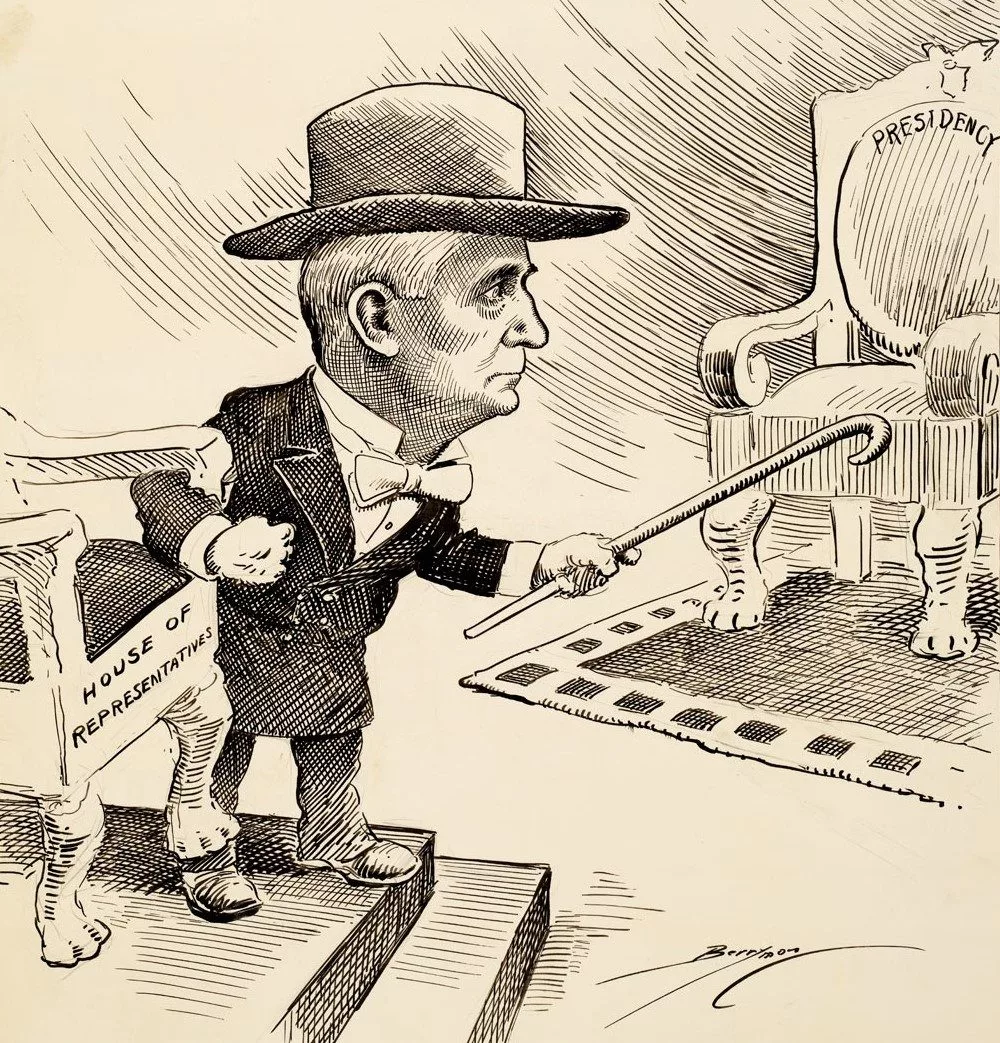

Pike County Congressman Champ Clark had supported Folk in 1910, but saw a pathway to the nomination when he ascended to Speaker of the House a year later.

With only weeks before the 1912 Democrat state convention on Feb. 20, the prospect of two men seeking the job caused panic among party leaders.

Folk supporters considered the 1910 pledge binding. Clark proponents said it was water under the bridge.

For his part. Clark had not even formally announced his intentions, but there was no doubt he wanted the nomination. Feelings between the two factions were “growing more bitter daily,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

Several suggested a statewide primary. Others noted that such an election could lead to a flood of office seekers.

“If a primary is held, it should be open to any man who cared to try,” said Congressman Joshua Alexander, who attended Northeast Missouri’s Culver-Stockton College and would later serve as Commerce Secretary. “It would be a good joke if some dark horse carried off the plum.”

A primary was discounted after the cost was estimated at $50,000 – almost $1.3 million now – which the party would have to pay.

“I hope they will get together and settle the question among themselves,” said Congressman Charles Booher, a Folk proponent.

The Louisiana Press-Journal reported all was hunky dory at the 1912 Jackson Day Dinner in Washington on Jan. 8. Speakers included Folk, Clark and another presidential aspirant, New Jersey Gov. Woodrow Wilson. Regardless, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch predicted “a lively fight” in Missouri.

The Speaker remained coy about his candidacy, but his attitude came at the same time that a “Clark for President” club formed, It planmed to “ignore absolutely the candidacy of Folk and the pledge made to him,” the Kansas City Times reported. Clark was “the only man with whom it is possible to win,” the committee wrote.

The Press-Journal was upset at the bickering, and worried that Democrats were throwing away a “great chance” to, for the first time, elect a home-state man as president.

“It is pitiful that this untimely brawl in Missouri should stand as a stumbling block in the way,” it noted.

The Times said Clark was in an “unenviable and embarrassing position” because of party stalwarts.

“They have put him in the attitude of breaking his party platform pledge and stirring up the worst factional fight the Missouri Democracy has known for years,” it wrote.

The Kansas City Post agreed, but added a thought with which Folk and Clark probably did not abide.

“The identity of the man is of secondary importance,” the paper concluded. “It matters little who he is, but it matters much to every citizen of the state, regardless of politics, that the next president of the United States hail from Missouri.”

Next time: A brokered solution.

CUTLINE FOR PHOTO:

An editorial cartoon by Clifford Berryman shows Champ Clark firmly attached to the House of Representatives while contemplating a bid for president. (National Archives).