LOUISIANA, Mo. — Defiance by a Pike County clergyman led to an enduring lesson about freedom of speech.

In an era when censorship has exploded – especially of Christian principles declared bigoted by fanatical, intolerant woke theorists – the fight waged by Father John Cummings almost 160 years ago should be an eye-opener on what can happen when constitutional rights are subverted.

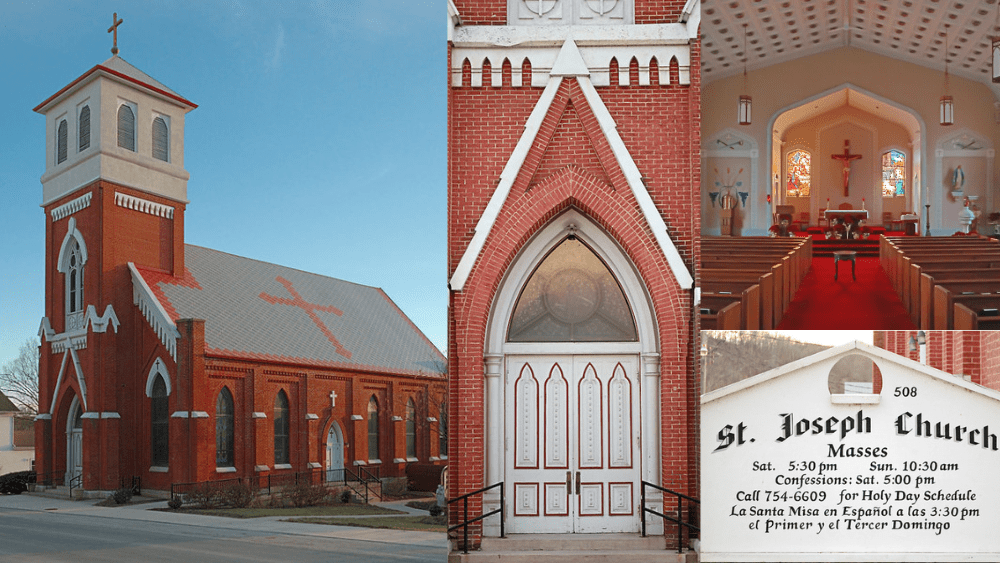

The Louisiana priest set off a firestorm when he said Mass at St. Joseph Catholic Church on Sept. 3, 1865.

His “crime” was preaching without having taken the loyalty oath required in a new state constitution enacted by lawmakers and narrowly approved by voters at the end of the Civil War.

“Cummings’ resistance to ideological thought control made him something of an instant celebrity,” The Rev. Donald Rau wrote in “Three Cheers for Father Cummings.”

Loyalty pledges were nothing new in America. The federal constitution itself requires some government officials to swear allegiance.

The 1865 Missouri oath was different because it clearly was a vindictive measure aimed at keeping people who had supported the Confederacy from holding public office, working in certain professions or voting. The 194-word affirmation contained 86 acts of alleged disloyalty.

In the months after Cummings was thrown in jail, more than 60 other Catholic and Protestant clergymen were indicted.

“I believed it to be wicked thus to surrender the claims of Christ to the demands of Caesar, and resolved, at the hazard of fines and imprisonments, yea, even of life itself, that I would refuse compliance with this unrighteous requirement,” said the Rev. Berry Hill Spencer, a Methodist preacher from Montgomery County.

A Pike County judge found Cummings guilty and fined him what would today be more than $7,500.

The case was appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, whose three justices had taken the oath. They voted unanimously against Cummings, and the ruling was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The priest’s arguments remained the same – that his rights were violated because the oath retroactively punished him for something which was not a crime at the time; that a legislative act had been used to declare him guilty without a trial; and that his freedom of religion had been infringed.

The case “engaged the attention of the ablest lawyers and jurists” and “the deepest interest was felt throughout the whole country,” wrote historian William M. Leftwich.

The nine justices heard arguments on March 15, 1866. The ruling came down on Jan. 14, 1867. Cummings won, but only by a 5 to 4 vote.

Writing for the majority, Justice Stephen Field said the oath was of “objectionable character” and tended to “subvert the presumption of innocence and alter the rules of evidence, which heretofore, under the universally recognized principles of the common law, have been supposed to be fundamental and unchangeable.”

Such oaths “assume that the parties are guilty; they call upon the parties to establish their innocence; and they declare that such innocence can be shown only in one way – by an inquisition, in the form of an expurgatory oath, into the consciences of the parties,” Field added.

The Missouri Supreme Court “reluctantly accepted” the higher court’s ruling, but “drew a distinction between voting and the practice of a profession,” wrote author Joseph A. Ranney.

State lawmakers repealed the oath in 1871. Four years later, a new constitution was adopted without it.

Cummings was given another pastorate. He served St. Stephen’s parish at Indian Creek near Monroe City before falling ill in September 1870. He died at age 33 on June 11, 1873, and is buried at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis – not far from the grave of another freedom fighter, Dred Scott.

The Supreme Court would deal with many more cases addressing loyalty oaths over the next century, often siding with the rights of the people over the desires of government. Justice Hugo Black called the Cummings case “one more of the Constitution’s great guarantees of liberty.”

Perhaps one Baptist elder said it best. The Rev. James Duval had also been jailed in 1865 for not taking the oath, and summed up the thoughts of many who sided with Cummings – the law could temporarily place people in shackles, but it would never imprison the Word of God.

“After the decision in the Cummings case, we were all discharged from custody, and are still engaged in trying to preach Christ – the Way, the Truth, the Life – to sinners,” Duval triumphantly declared.

In the featured image: St. Joseph Catholic Church in Louisiana, site of a famous freedom of speech case.