Just three years later, his vitriolic prattle would undermine a Pike County icon.

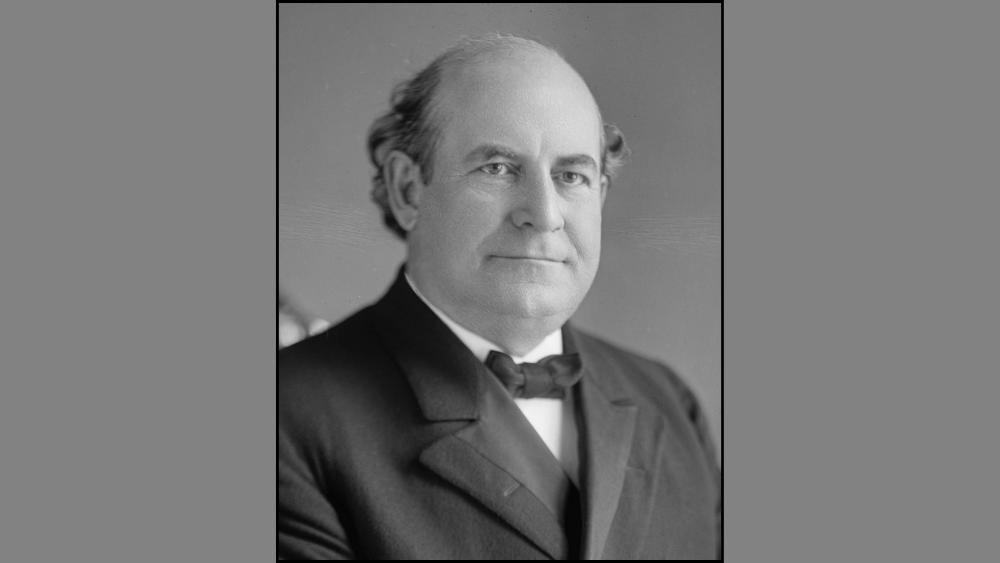

But in the summer of 1909, William Jennings Bryan had nothing but praise for Champ Clark, and reassuring advice for those who heard his Bowling Green speech.

The Nebraskan was coming off a third unsuccessful bid for the nation’s top political job, yet retained huge influence in the Democratic Party. The visit was part of a lyceum tour of the Midwest.

In two years, Congressman Clark would ascend to third-in-line for the presidency and would inevitably fight for it in 1912.

Things were more congenial in 1909. The later turnaround would seemingly prove the point of future Missouri President Harry Truman, who urged those that want a friend in Washington to get a dog.

Reserved tickets for Bryan’s speech cost 75 cents – about $21 today – and went on sale June 7, eight days before “The Great Commoner” was due. Proceeds were to benefit Pike College, which since 1881 had offered instruction in the classics so beloved by Clark and Bryan. Clark’s wife, Genevieve, taught there.

Marketing was handled by Lulu Collins, a trailblazing Louisiana attorney and administrator at the college. The scrappy suffragist had campaigned for Clark during his first congressional election in 1892, even though the law then or 17 years later did not allow her to vote.

Bryan’s Short Line train pulled into the Bowling Green station at 12:10 p.m. on June 15.

“The depot was crowded with people when he arrived and his reception was certainly cordial,” the Bowling Green Times noted.

The newspaper downplayed Bryan’s inability to win the presidency, saying defeat “does not remove the love from the hearts of the people,”

Collins, Pike County School Commissioner Willa Mitchell and the Rev. E.M. Richmond took Bryan to a 90-minuite meet-and-greet at the home of Jefferson Davis Hostetter, a Bowling Green lawyer who would later serve as a state lawmaker, judge and chairman of the commission that erected a statue of Clark at the Pike County Courthouse.

“The reception was held in the shade of the beautiful trees on the lawn where carpets were spread and seats provided,” the Times said. Hostetter’s wife, Mary, and daughter, Lily, helped greet “the stream of people” who came calling and “made everyone feel at ease.”

The town band was playing when Bryan got to the opera house on the square at 7:30 p.m. The Times said the large crowd “pressed forward, everyone eager to shake his hand.”

“When the ovation given him was ended, Col. Bryan opened his address with complimentary remarks for Hon. Champ Clark,” it noted.

Bryan’s address was entitled “The Price of a Soul,” and was delivered with what the Times called “a clear and distinct voice in language that a child could understand.”

Most expected the speech to be political, but Bryan instead offered “a talk along the lines of right living” in all aspects of life.

“He quoted the words of Christ: ‘What will it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul?’” the Times wrote. “The lecture pictured the real successful life, the life that brought happiness, and compared it to the life of men who became so wrapped up in money making that they neglected their families and decay was the result.”

Bryan also warned America “against going to destruction on the same rocks that had destroyed other great nations – greed for power, for gold.”

The paper called it a “grand lecture” in a style that only Bryan could have pulled off.

“With a heart in touch with the masses, he talks feelingly,” it said. “It makes no difference what you think of Col. Bryan politically, no one surpasses him in ability and sympathy for the masses.”

Bryan might have been a little preoccupied. The lyceum tour came at a time when some Democrats were asking him to step aside and let others lead the party. The Bowling Green stop also came the same day as the announcement that his son, William Jr., was getting married.

In any event, Bryan traveled to Chicago the day after his Pike County appearance to meet with top Illinois Democrats.

Disagreements with Clark would lead Bryan to back New Jersey Gov. Woodrow Wilson for president during the 1912 Democratic National Convention. Clark, who would serve as Speaker of the House until 1919 and die at 70 in 1921, blamed Bryan for the defeat.

Bryan initially served as Wilson’s Secretary of State, but resigned after a dispute with the president on June 8, 1915. He later participated in the Scopes trial on the teaching of evolution and died at 65 on July 26, 1925.

In 1914, a longer version of “The Price of a Soul” was published. It can be found at www.archive.org.