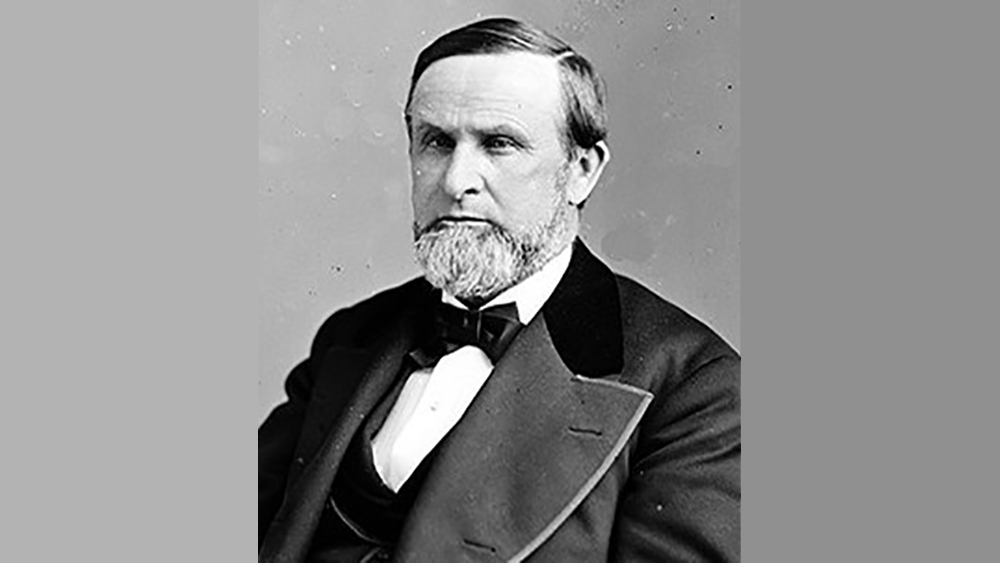

PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — The task looked impossible, but Aylett Hawes Buckner took up the challenge.

The Bowling Green newspaper editor, lawyer and judge was among more than 100 delegates to the 1861 Peace Convention in Washington, D.C.

The goal was to find a compromise over slavery with which everyone could agree. In hindsight, it was wishful thinking, but the fact that such a gathering occurred at all was remarkable.

The country was in chaos, with seven states having already seceded. Neither Republicans nor Democrats were willing to compromise. There were also questions about the constitutionality of having unelected delegates dictate national policy.

Outgoing President James Buchanan supported the convention. “Convinced that Congress would not hold the Union together, he desperately reached out for any alternative that seemed even remotely plausible,” wrote William J. Cooper in “We Have the War Upon Us.”

President-elect Abraham Lincoln disagreed, telling a friend that “no good results” would come of it and predicting it would break up “without having accomplished anything.”

John Tyler, who was almost 71 years old, came out of retirement to lead the convention. Among those accompanying the former president to Washington were his 40-year-old wife, Julia, and their eight-month-old daughter, Pearl.

Joining Buckner in the Missouri delegation were St. Charles County lawyer John D. Coalter, Liberty attorney Alexander W. Doniphan, former State Representative Harrison Hough of Charleston and former Seventh Judicial Circuit Judge Waldo P. Johnson of Osceola.

As with Buckner, most of the delegates were attorneys. Author Mark Tooley identified six former cabinet members, 19 former governors, 64 men who had served in Congress and 12 state supreme court justices.

The convention got under way at noon Feb. 4 in Willard Hall, a former Presbyterian church. Ironically, the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America met for the first time that day in Montgomery, Ala.

Buckner was a Democrat and staunch supporter of the 10th Amendment’s guarantee that left to the states all rights which were not specifically outlined in the Constitution. He would prove his point during the convention.

As with Tyler, Buckner was a Virginia native from a prominent family. He was born at Fredericksburg on Dec. 14, 1817. His mother, Mildred, was “a woman of strong mind and extraordinary energy,” according to author Phineas Camp Headley. His father, Bailey, was an officer in the American army during the War of 1812 and later worked in the Treasury Department. He was “a most brilliant and popular man,” a family history reads.

Thanks to a physician uncle for whom Buckner was named, he attended Georgetown and the University of Virginia. He taught school and studied law before moving to Missouri in 1837.

“Here he acted as Deputy Sheriff and Deputy Clerk during the day and studied law at night until he was licensed to practice by the Supreme Court in 1838, and Pike county was the theater of his first efforts in his profession,” Headley wrote.

A nasty divorce case involving Isaac Newton Bryson, the son of a Louisiana co-founder, and his wife, Margaret, propelled Buckner to legal stardom.

“The facts of that case partook more of the character of romance than real life, and it excited great interest in the eastern part of Missouri,” Headley noted.

In 1841, Buckner took office as Pike County Circuit Clerk. He also married Virginia native Eliza Lewis Clark, whose father was a first cousin of famed explorer William Clark and Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark. Her mother was a first cousin of Meriwether Lewis.

Buckner declined to run for a second term and in 1850 moved to St. Louis.

He didn’t like city life and by 1855 was back on his Pike County farm. Buckner served on the Missouri Board of Public Works and in 1857 was elected judge of the Third Judicial Circuit, which covered Pike, Lincoln, Montgomery, St. Charles and Warren counties. It was while serving in that capacity that he was chosen for the Peace Convention.

After almost two weeks, a pro-Southern package of six constitutional amendments and four Congressional resolutions was proposed. Northerners were outraged. One of the recommendations went as far as saying that Congress could make no future constitutional amendments outlawing those approved by the convention.

Delegates met with Lincoln a few days later, and it didn’t go well. The president-elect adamantly said there would be no compromise on the extension of slavery, calling any attempt “surrender.”

Lincoln said no concession “short of everything worth preserving and contending for” would satisfy the South. And while he still wanted peace, “it may be necessary to put the foot down.”

PART 2

A Pike County judge who was part of a last-minute effort to avoid war offered a proposal which followed his view that states should have greater power than the federal government.

Aylett Hawes Buckner, a descendent of George Washington, was part of the February 1861 Peace Convention. He was among five Missouri representatives chosen by state lawmakers.

The gathering drew media ridicule, first for meeting behind closed doors on opening day and then for what most newspapers viewed as a lack of urgency.

Delegates were “evidently under the impression that time and calm reflection are the best panaceas for the sick patient,” wrote the Alexandria Gazette.

The Washington Evening Star reported that “fervent prayer” for success was offered in local churches, even though people on both sides of the slavery issue seemed bent on “defeating all practicable plans of conciliation.”

Author Mark Tooley later called it “a desperate attempt to protect slavery and assuage Southern worries about Northern Republican encroachment on Southern political prerogatives.”

Some papers began to call the gathering “The Old Gentlemen’s Convention” due to the long list of elderly former officeholders.

Delegates spent almost three weeks wrangling over proposals, most of which in some manner would have allowed slavery to continue. On Feb. 24, President-elect Abraham Lincoln again made it clear he would not support extending slavery to new territories.

Two days later, Buckner offered an amendment. He voiced concerns about states’ rights and the danger of unlimited federal oversight.

His proposal ensured the feds would not have “power or authority to coerce or to make war directly or indirectly upon a State, on account of a failure to comply with its obligations.”

The motion failed, and on Feb. 27 delegates adopted seven recommendations that were sent to Congress for approval as a constitutional amendment. Slavery would be protected where it existed, but the proposal featured codicils that would have led to its eventual end.

The Missouri delegation voted against the plan and the U.S. Senate rejected it. The House refused to even consider the measure. Lincoln took office on March 4 and on April 12 the Civil War began when Confederates fired upon Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

Author Phineas Camp Headley wrote that Buckner “held no public position” during the conflict. Buckner moved to St. Charles in 1862 to oversee a tobacco operation and other business interests, and later became a resident of Mexico, Mo.

In 1872, Buckner was a Missouri delegate to the Democrat National Convention which nominated newspaper publisher Horace Greeley and Missouri Gov. Benjamin Gratz Brown for President and Vice President, respectively. They were trounced by the Republican ticket of Union war hero Ulysses S. Grant of Illinois and Massachusetts U.S. Sen. Henry Wilson.

That same year, Buckner was elected to Congress. The country was headed for a financial crisis that would last six years, and Buckner fought for reduced taxes.

As with many lawmakers of the era, Buckner probably would be viewed today as a racist. Some of his comments definitely qualified. However. a look at the record indicates his opposition to the 1875 Civil Rights Act was more practical than problematic.

Buckner argued that the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution voided need for new legislation concerning African-American rights.

“If he is not the equal of any other man before the law, in what does his inequality consist?” he asked on the floor of the House. He said it was “not civil rights but social rights that (the measure) seeks to enforce and protect.”

Buckner also raised concerns about inclusiveness, saying the bill specifically targeted one race. In a speech the same day, African-American Congressman Robert Brown Elliott of South Carolina noted that the legislation would “determine the civil status, not only of the negro, but of any other class of citizens who may feel themselves discriminated against.” It eventually was approved by a vote of 162 to 99.

Even in troublesome moments, Buckner could be philosophical, as when he said that the “accumulations of a lifetime disappear like snow before a summer’s sun, and the millionaire of today is the bankrupt of tomorrow.”

Buckner did not seek re-election in 1884 and retired. He died at 77 in Mexico, Mo., on Feb. 5, 1894, and is buried there.