PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — James Carson Jamison had the kind of wanderlust that prompted him to get out of Pike County as quickly as he could.

But, as with many who roam far and wide, he came back. Best of all, he chronicled his experiences as part of an ill-conceived and disastrous effort to expand American influence.

“In the days of my boyhood, the youths of my native state glowed with an ardor for journeying into far places in search of fortune and stirring adventure,” he wrote.

Jamison was born on a farm that one publication called a “wild tract of land” along Guinn’s Creek southeast of Paynesville on Sept. 30, 1830.

He was the 10th of 12 children to John Cowden and Margaret Torrence Jamison, who had married in North Carolina before moving to Missouri in 1827. Older siblings Margaret and Adam, and younger brothers, Alexander and J.C., were also born in the Show-Me State.

From early on, Jamison appeared restless. He was a fiery teenager living with a Pike County cousin when the Mexican War erupted in 1846.

“I was wild to reach the army and enlist, but two handicaps opposed me: I had no horse nor money with which to buy one,” Jamison noted.

Railroads and telegraphs had not reached Pike County, so getting around without a steed meant walking long distances. A third factor was Jamison’s age.

“Despair settled upon me at the prospect of remaining in the monotony of farm life,” he admitted. “I never entirely lost hope, however, that something would turn up to carry me to strange lands.”

Every chance he got, Jamison went into Paynesville and listened as the men of the community talked about the war. It was there that he heard about an infantry company in Troy that was seeking recruits.

Jamison borrowed a horse from a local doctor and rode to Lincoln County, where, despite his age, he was accepted and took the oath. His joy soon turned to sadness when President James Polk revoked the recruitment order.

“This was the bitterest grief that had come to me since the death of my father in 1845, which had scattered his children among strangers,” Jamison said.

The anguish didn’t last long. In 1849, the six-foot-tall, 170-pound Jamison joined a party headed by wagon to California. They crossed the Missouri River on April 5. Jamison later caught up with another westbound wagon train, which included a steamboat crewman and a future Civil War general. They arrived in Sacramento on Oct. 9.

Jamison lived and worked in such mining camps as “Rough and Ready” in Nevada County and “Todd’s Valley” in Placer County. The primitive camps were so isolated that news was at a premium, with a two-cent paper going for a $1 pinch of gold dust.

“Frequently he walked ten miles afoot to meet the stage coach to get The Republican, a St. Louis newspaper, and paid a dollar per issue,” according to an article in the Chronicles of Oklahoma.

It was while panning for gold that Jamison first heard about William Walker, a Tennessee lawyer and journalist who had aspirations of colonizing lands south of the American border.

Walker’s first foray came in the summer of 1853, when he sought permission to create a colony at the port of Guaymas in northwestern Mexico.

Walker reasoned that the city’s location 250 miles from the U.S. border would make it a good buffer against Indian raids in Sonora. The Mexican government sent him packing.

On Oct. 15, 1853, Walker set out with 45 men to capture La Paz in Baja. He quickly declared it capital of the new “Republic of Lower California” and made himself president. One of the commander-in-chief’s first actions was to make slavery legal.

The Mexicans were not amused. Walker was finally forced to retreat back to San Francisco, where he was arrested and tried for conducting an illegal war. A jury acquitted him.

On Dec. 29, 1854, a newspaper friend of Walker’s got Nicaraguan President Francisco Castellon to sign a colonization grant giving 300 Americans the right to live in the Central American country, where a civil war was in progress. Castellon wanted Walker’s help in thwarting his enemies. It was just the kind of action for which Jamison had been waiting.

“My blood grew hot at the thought of the stirring adventures that awaited me if I could attach myself to Walker’s army,” he said.

In December 1855, Jamison met in San Francisco with representatives of William Walker, a Tennessee doctor, attorney and journalist who wanted to set up English-speaking, slave-holding colonies in Central America.

“At this age I looked upon life with an enraptured eye; its every prospect charmed me, and in my exuberance of health and strength I asked no odds of time nor fortune,” Jamison later wrote.

On the third day at sea, Jamison was overwhelmingly elected first lieutenant by the 46 men who planned to join Walker, even though most of them were strangers.

Upon arrival, Jamison was summoned to the commander’s headquarters. The author said he never saw the “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny” smile or wear a military uniform.

Walker was a soft-talking, tee-totaling, well-read, disciplined man who was just as likely to order a death sentence for anyone who insulted a woman as for committing a crime. He was so stern that he once reduced in rank his own brother, Norvel, for breaking military rules. Jamison saw the bad, but also the good in Walker’s character.

“Men like Walker have their faults, and these are accentuated when they fail; their virtues sink into the grave with them,” he wrote.

Two years earlier, Walker had tried unsuccessfully to establish a colony in Western Mexico, but hoped for a better outcome in Nicaragua. Walker contracted with Nicaraguan President Francisco Castellon to provide military support.

Jamison’s outfit saw action almost immediately upon reaching the country, which was a key shipping route between New York and San Francisco. As with the Mexicans, Castellon’s detractors weren’t happy about gringos laying claim to their land, even with a presidential decree.

Jamison’s company fought at several locations, including Rivas, LaVirgen, San Jorge, San Juan del sur and Granada.

It was during the first Battle of Rivas on April 11, 1856, that Jamison was shot in the right leg. Surgeons ignored him because there were other soldiers who needed greater attention.

Of particular note was the gallantry of one captain from New York. He stuck his arm around the corner of a building to fire a pistol, only to have an enemy bayonet thrust through the limb followed by the sound of the attached rifle blowing it to bits.

The captain “withdrew his shattered arm with proper haste, and gazing at it with immeasurable disgust, remarked dryly: ‘The damned rascal got my pistol,’” Jamison wrote

Knowing that “capture meant death,” Jamison crawled from the street into an unfinished cathedral, bullets dinging off the church’s bell. He fell asleep and woke in pain several hours later. Deciding to retreat, Jamison slowly made it back to his company, barely escaping enemy patrols.

The Pike County native witnessed other brutalities and oddities of war. At Masaya, he saw “scores of the enemy shot down while holding up their hands in token of surrender.”

In another battle, an American soldier was struck by a bullet to the head that “killed him so instantly he never moved.”

“I did not have the least suspicion of what had befallen him until orders were given to with-draw to a position of greater safety,” Jamison wrote. “Then it was found that the poor fellow was still grasping his rifle, as if taking aim.”

At some point, William Walker’s effort to establish American influence abroad became more about expanding the slave trade than winning hearts.

Pike County native James Carson Jamison, who joined Walker’s men in backing the government of Nicaragua in a civil war for control of vital shipping routes, admitted as much. But he disagreed with the commander’s critics, who said the decision had been made before Walker left for Central America in May 1855.

By July 1856, Walker had inaugurated himself as Nicaraguan president. The honeymoon was brief, because tensions reignited in September, when five Central America republics agreed to ban slavery.

Walker tried to gain financial support from Southerners back home by revoking the edict. He also declared all property of enemies forfeited to the state.

“In our frequent social and business intercourse, we often discussed the conditions of Nicaragua, as well as our own hopes and ambitions, yet in none of these conversations was it ever intimated by any one that African slavery was a preconceived purpose or active motive in the coming of Walker to Nicaragua,” Jamison wrote.

Despite Walker’s claims, the governments of other Central American countries soon turned against him. In addition to upsetting Nicaragua’s neighbors, Walker made a critical mistake by drawing the ire of American businessman Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The shipping mogul had established a very profitable company that took passengers across the Nicaraguan isthmus. Walker decided to take control of the magnate’s fleet. Vanderbilt vented his wrath by sending guns to Walker’s enemies and agents to organize opposition.

The enemy caught up with Walker’s dwindling army at Rivas, and proceeded to blockade the city from November 1856 to May 1857.

Supplies became so short that the Americans were “reduced to mule meat for subsistence, and even this tough and unpalatable food was hourly growing more scarce,” Jamison wrote.

The stress of near-constant conflict began to take a toll. A lieutenant, described by Jamison as a “hot-headed Virginian,” got into a fight with an unidentified captain over eating a cat. The lieutenant “shot the captain dead,” Jamison said.

Surrounded and outnumbered seven to one, Walker finally agreed to a settlement that allowed him and his men to go to Panama.

Walker would be tried and acquitted for neutrality violations. On Aug. 6, 1859, he and a force of 91 men landed in Honduras and captured the city of Trujillo with the intention of marching on to Nicaragua. They wouldn’t make it.

The Honduran army killed 60 of Walker’s men, and just about all of the survivors were wounded. Jamison was fortunate not to be among them. He had already returned to America. On Sept. 12, 1860, Walker was executed by firing squad.

The commander had drawn criticism for being an ineffective military leader, but Jamison says Walker showed “indomitable courage” and had a “contempt of danger” with a “supreme detestation of everything low and mean.”

“The opinion may be risked that had he lived and the fortunes of war sustained his cause, he would have changed the political history of Central America, and made the five Central American states a land of intellectual progress and commercial greatness, and saved them from being a hot-bed of ever-recurring revolutions, and the abiding place of social disorder and commercial poverty,” Jamison wrote.

Pike County native James Carson Jamison provided historical context to a calamitous attempt at colonization in Central America.

The Paynesville man fought under William Walker, a resolute Tennessee aristocrat bent on reigniting the slave trade.

Walker was executed seven months before the first shots of the Civil War, but was regarded as a hero in the South. Cultural references still abound. Margaret Mitchell mentions him in “Gone With the Wind” during a conversation involving Rhett Butler.

Two movies, “Burn” starring Marlon Brando in 1969 and “Walker” with Ed Harris in 1987, loosely describe his story.

There are several written accounts of Walker’s exploits, including Jamison’s. The book is entitled “With Walker in Nicaragua, or Reminiscences of an Officer of the American Phalanx.” It was released in 1909 by the E.W. Stephens Publishing Company of Columbia and is available now online.

“The publication of this volume is a rare contribution to the written history of one of the most romantic and disastrous undertakings that ever appealed to the imagination of any man in search of renown and fortune,” declared the San Francisco Call in its review.

The author reflected upon misconceptions he says developed after Walker’s death and the disbanding of those who fought with him.

“Popularly, the opinion is that these men were renegades and marauders who went to Nicaragua solely to satisfy their greed for pillage and plunder, and derisively the name ‘Filibusters’ has been applied to them,” he wrote.

While admitting that some soldiers took advantage of the situation, the Americans “as a whole respected the rights of property, the sanctity of domestic relations and the sacredness of life itself as honorably as would be possible in any civilized country in time of war.”

Jamison returned to Pike County in 1857 and served as a captain in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. He was taken prisoner after the Battle of Lexington in September 1861 and confined to a Union jail.

During a furlough, Jamison married Sarah Ann White of Clarksville on June 10, 1862. Their first child died as an infant in 1869. A daughter, Ann, was born in 1875.

Lingering problems from at least four bullet wounds, which the author described as resulting from a “truculent youth,” forced Jamison into a quieter life.

In 1867, he and a partner bought the Clarksville Sentinel newspaper. Seven years later, the Riverside Press of Louisiana was added. Jamison sold the paper to a 30-year-old lawyer named Champ Clark in 1880, and the same year bought the Bowling Green Express, changing its name to the Times.

Jamison later served as Missouri adjutant general under governors John S. Marmaduke, a former Confederate major, and Albert P. Morehouse, who served in the Union militia during the Civil War.

The youthful spirit that had driven Jamison as a teen returned in 1889, when the family moved to Oklahoma, where he published the Guthrie Democrat, served in government and organized the state’s first militia.

“In contrast to the activities of his early life, this brave, honest and chivalrous man’s later years were tenderly associated with nature’s gentlest creatures, the birds,” wrote The Chronicles of Oklahoma in March 1943. “He wrote pages of newspaper letters pleading for their care and protection, and for the enactment of laws under which they might find shelter, and was a moving cause in the organization of the first state Audubon society.”

On April 11, 1911, three old men gathered for a reunion outside of Los Angeles. They were the last known surviving members of Walker’s warriors. Jamison would outlive the other two, dying on Nov. 19, 1916, at age 86.

Apparently cured of his restlessness, Jamison was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Clarksville. His wife would join him upon her death at age 87 on Feb. 5, 1930.

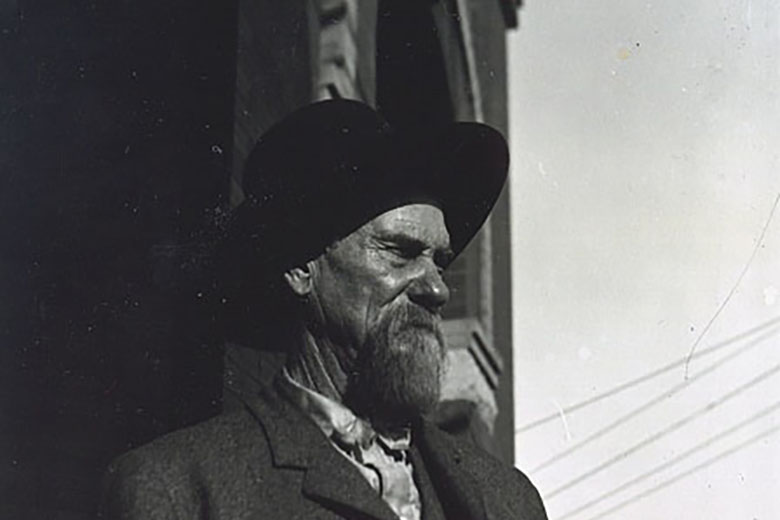

“In repose his expression was one of resolution and determination, beginning at the tip of his iron-like brow and extending to the line where his mane of white hair began mantling his brows,” wrote The Chronicles of Oklahoma. “There was something lion-like in his bearing and one would feel that it was unwise and dangerous to provoke his anger, yet with a smile he would extend his hand in greeting, his face indicating kindness.”