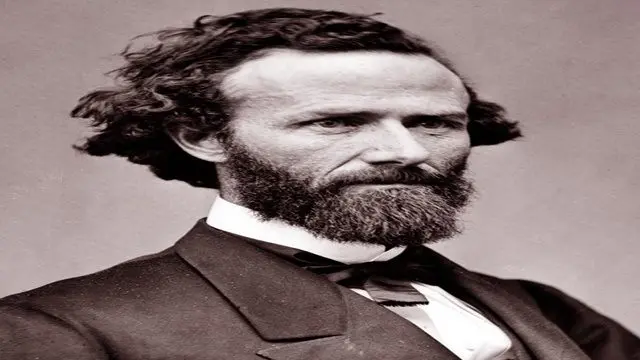

It was a modest sentence that would have unprecedented consequences. In January 1864, Missouri U.S. Sen. John Brooks Henderson of Louisiana introduced what would become the 13th Amendment. It simply said: “Slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, shall not exist in the United States.”

For a man who could talk about a single issue for hours, it was a blunt edict. While other proposals had been made, Henderson’s would be what author Michael Vorenburg called “the foundation of the final amendment.”

The move was remarkably audacious for a former slave owner who had witnessed the Civil War’s carnage. At the time, the Constitution hadn’t been changed in six decades. The last update had been rather innocuous – requiring the president and vice president to be elected together rather than having the defeated person serve in the secondary role.

At first, few believed Henderson’s measure would pass. The amendment “appears to us like kicking a dead man,” the Nashville Daily Union intoned.

But the senator stuck to his guns, convincing colleagues and others that “the inalienable right of liberty belongs to all men.”

“This proposition is to mark an epoch in the history of our country if it shall be adopted, and I take occasion now to express my sincere wish that it may become a part of the Constitution of the United States,” he said.

Henderson had many champions in his quest, not the least of whom was Abraham Lincoln. The senator and the president had been close confidantes since Henderson came to Washington in 1862.

Lincoln had told Henderson about his plan to issue the Emancipation Proclamation eight months before doing so. The senator proved a vocal advocate for the president’s emerging views on methods to free the slaves. Lincoln said the amendment’s straightforwardness would cover any objections.

In February 1864, the Senate Judiciary Committee added to the punishment clause of the amendment and drafted jurisdictional guidelines. Versions authored by Henderson and Representatives James Ashley of Ohio and James Wilson of Iowa were merged. The final draft was approved in the Senate on April 8, 1864. The House followed on Jan. 31, 1865.

One day later, Illinois became the first state to ratify. Missouri did so within a week. The amendment was declared in effect after Georgia approved it on Dec. 6, 1865.

Before his assassination in April 1865, Lincoln had called passage a moment “of congratulation to the country and to the whole world.”

A strict constitutionalist, Henderson had been explicit about the consequences if slavery remained.

“History will repeat itself,” he said. “New wars will come. The innocent will suffer again. Shall we then leave slavery to fester again in the public vitals?”

The book “Abraham Lincoln and the Battles of the Civil War” credits Henderson “with rare courage and skill” for his efforts. Author Alexander Tsesis calls the 13th Amendment “monumental” because America had “committed itself to promoting freedom through a national mandate.”

“This was no formulaic act; it created a constitutional obligation to preserve and further liberty rights,” he wrote.

In 1907, the Magazine of History noted that Henderson “was at every stage of the struggle conspicuous for the courage, sagacity and unwavering confidence with which he accepted, on behalf of the most important of the border states, whatever the new progress of the nation into light and liberty required.”