Editor’s note: Following is the final part of a story series by contributing writer Brent Engel.

The trial that was supposed to resolve questions in the March 1915 death of former Louisiana Mayor Alten Walker did just the opposite.

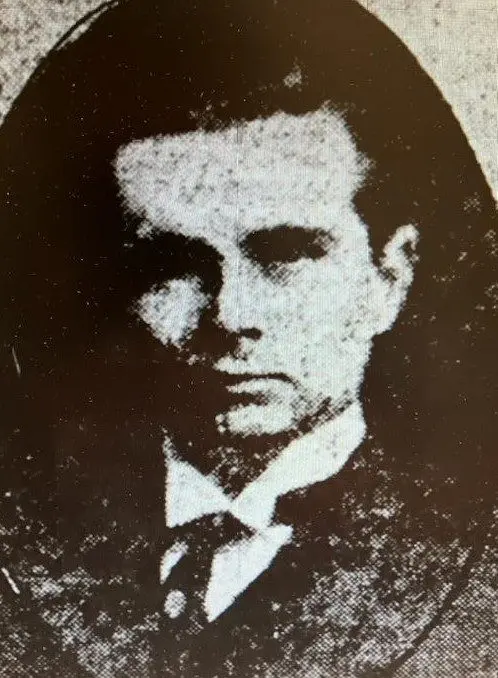

Twenty-six-year-old real estate agent Fred Wilkins was charged with murder for shooting Walker in the stomach.

Before dying, the 46-year-old staff member of Missouri Gov. Elliott Major repeatedly said it was an accident. Both men swore they were handling the gun at the same time when it fired.

After months of delays, a jury finally was impaneled in January 1916 before Judge Edgar Woolfolk. The Gillum Opera House in Bowling Green substituted for the county courthouse, which had been destroyed by fire in October 1915.

A twist in a case that seemingly had an endless supply came a week before the proceedings. Wilkins was busted for fraud, accused of bilking Anna Doyle of Hannibal by giving her a bogus promissory note in exchange for an $800 cash loan – the equivalent today of $25,000. Wilkins pleaded not guilty.

Pike County Prosecuting Attorney Tom McGinnis faced an uphill battle in the Walker case. Other than Wilkins, there were no direct witnesses. More than a dozen men who saw a wounded Walker shortly after the shooting heard him exonerate the suspect. There were also three missing elements.

The first was the disappearance of a prosecution witness who had claimed he heard a shot at Wilkins’ house the night of the incident. That would have contradicted the story by both of those involved that Walker was wounded in his office.

The second was the gun. Authorities had not collected the .38-caliber revolver at the scene and it could not be found.

The third was that Wilkins, as he had from the start, refused to testify.

McGinnis was left to argue that the desperate suspect and his wife, Diane, blackmailed Walker for money, lured him to their home and shot him when he refused to cooperate.

There was one problem with the theory. As a friend, Wilkins would have certainly known that Walker faced huge financial troubles of his own and was a poor candidate for extortion.

Instead, McGinnis put on the stand witnesses who said they saw a disheveled Walker accompanied by Wilkins the night of the incident. He also tried to show that Walker’s clothing indicated the shot had been deliberate.

“The evidence will show that the bullet had passed only through Walker’s shirt, and that he had been disrobed at the time he was shot,” McGinnis said. “The bullet did not pass through his coat, vest or trousers.”

Wilkins’ attorneys, Ras and Eugene Pearson, repeated the claim that the shooting was unintentional and that there was no motive.

“Walker was a man of strong character,” Ras Pearson said. “He had many friends, many enemies. He knew best of all how he was wounded, and he repeatedly said that Fred Wilkins was in no way to blame for his death.”

McGinnis countered that Walker freed Wilkins from responsibility in an effort to protect his own reputation.

The opera house was packed with spectators, including Wilkins’ wife and two of the couple’s young children. Diane Wilkins also declined to testify, but she certainly spoke rather melodramatically to the newspapers.

“I never knew what it was to really live until I sat by my husband’s side and felt my heart beat with his as the different witnesses went upon the stand and told stories that might cost him his life,” she said.

Mrs. Wilkins added it was difficult to hear testimony against her husband, but that the Pearsons had told her to maintain decorum.

“I just kept on smiling,” she said. “It must have been a foolish smile. Possibly, it deceived the crowd, but I guess the women in the opera house, or courtroom, must have understood a little how I was feeling. It is an experience a woman can never forget. You just sit on edge all the time, and yet bound hand and foot by rules.”

After two days of testimony, the jury took three-and-a-half hours to acquit Wilkins. He and his wife shook hands with each juror. For the many who had hoped for greater detail, the outcome was disappointing.

“The scandal seekers at the trial did not get their money’s worth,” one newspaper reported.

It’s unclear what happened with the fraud charge. But, as with so many elements of it, the unpredictable nature of the shooting case carried over.

The same year of the incident, Wilkins began studying law. He was admitted to the bar in 1921 and spent the next 40 years practicing in Louisiana, including a stint as city attorney.

Wilkins died of an apparent heart attack at age 72 shortly before noon on June 19, 1961 – just as he was returning to his rural Louisiana home from a client’s court hearing in Bowling Green. As with Walker, he is buried in Louisiana’s Riverview Cemetery.

In 1916, the Pike County News had summed things up in a post-acquittal observance that could as easily have been more than a century later.

“The shooting of Walker remains as much of a mystery today as it has from the first, and there is little likelihood of it ever being cleared up.”