Editor’s note: Following is the first part of a story series by contributing writer Brent Engel.

Fielden Estes managed to stir up a ruckus even after he kicked the bucket.

The Pike County man probably would have enjoyed the battle that broke out after his passing at age 80 in September 1900.

Described as an eagerly combative, wildly eccentric and miserly penny pincher who could be a benevolent gentleman or a wretched jerk, Estes left an estate that would today be worth $10 million.

To be settled were financial claims from J.W. Crewdson, a prominent Louisiana doctor who took care of him, and Samuel Estes, an infirm brother who had been all but cut off.

“The consensus of opinion in Pike County appears to be that, though Estes is dead and buried near his old home in Calumet, his name will live on in the courts for many years to come,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch observed.

Estes was born in Kentucky on Nov. 24, 1819. The fourth of 13 children, he came to Pike County with his parents about age seven. His father, Robert, was a Virginia native and War of 1812 veteran who had married Elizabeth Griffith in the Bluegrass State.

The family farmed. While an unhealthy child who could barely read or write, Estes’ smarts came from common sense, observation and determination. Before age 30, he had made a bundle selling horses and making real estate loans, and was speaking like a highly-educated economist.

“You can talk about your ways of making money, but I tell you that the cent-per-cent way is the best,” he said. “There’s nothing beats cent-per-cent.”

“During his lifetime, he was a peculiar character, having few friends and a faculty for holding onto a dollar until the last possible moment,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat said.

Estes guarded his holdings, citing thrift as the reason he refused to take a bride.

“When I was a young man, I was too busy to marry,” he told one lawyer near the end of his life. “When I grew older and made money, I was afraid of women. I was afraid they would want to marry me for my money alone, and I wouldn’t have none of that sort of thing.”

However, the bachelor admitted nuptials had crossed his mind. An experiment quickly changed that. A good housekeeper and cook, Estes spent six months making an extra plate at every meal. The idea was to see how much having a wife would cost.

“Well, my wife ate too much, entirely too much, sir, and I concluded that a wife was too costly for me,” Estes told an interviewer. “So, I divorced the woman before I got her. Since then, I only serve one plate.”

Instead of a woman, litigation seemed to be Estes’ constant companion. The long list of Pike County attorneys who came across him over the years included former Missouri Supreme Court Justice Thomas James Clark Fagg; William Henry Biggs, who practiced in Louisiana for years before becoming an appeals court judge; Naval Academy graduate and unsuccessful congressional candidate Matthew Reynolds; William Hamilton Morrow, who had fought as a Confederate in just about every major battle of the Civil War; and former Missouri Lieutenant Governor David Ball.

Ras Pearson of Louisiana was another lawyer who represented Estes.

“He was good to those who were good to him,” said Pearson, who drew up Estes’ contested will. “He never forgot a man who did him a favor.”

“He never forgot an enemy, either,” Ball retorted. “Fielden Estes could hate with a virulent vindictiveness.”

Next time: A “personal matter.”

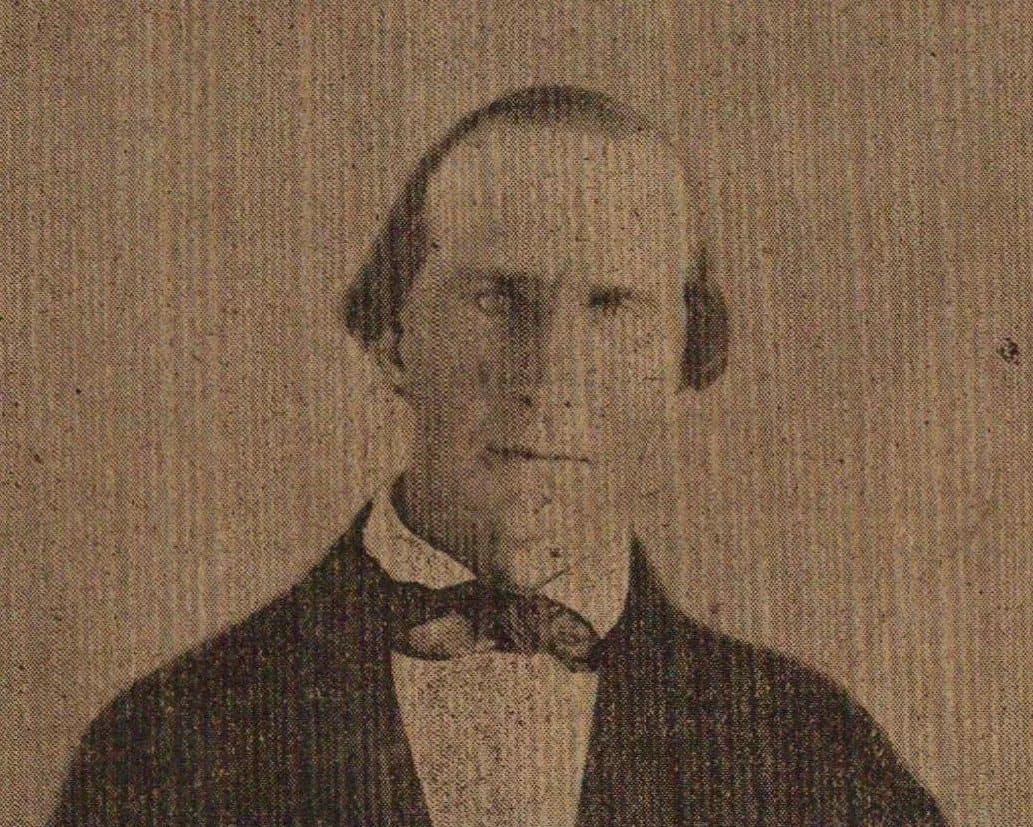

CUTLINE FOR PHOTO:

Fielden Estes