by contributing writer Brent Engel. Editor’s note: Following is the second part in a story series

Political nominee chosen in unusual way

It should have surprised no one that Missouri Seventh District Democrats controversially used a coin toss to choose an 1888 congressional candidate.

Years of political shenanigans, scurrilous attacks and brazen threats had led to the eight-county area being dubbed “The Bloody Seventh.”

One book claimed “the enthusiastic interest” of residents and “numerous hot and prolonged contests” by office seekers were to blame. To be elected, it said, a candidate had to “have an unresisting firmness of character, high ability, courage and tenacity as a fighter.”

Pike County Judge Elijah Robinson and attorney Richard Norton of Lincoln County certainly qualified. Their race for the congressional nod in 1884 started the ball rolling toward controversy in the next four years.

The Warrenton Banner couldn’t resist an archaic profanity in poking fun at Robinson and his raucous supporters.

“The wisest thing Judge Robinson can do would be to take a stuffed club and beat a little discretion into the heads of his damphool (damn fool) supporters,” it said.

Even with six others in the race, there were hopes that the Aug. 8 nominating convention in Montgomery City would go smoothly. The Middletown Chips said it was tired of “the biennial dog fight in the Bloody Seventh.”

Optimism was dashed when delegates deadlocked. Ideas to draw straws or toss a coin were rejected. So, a second contentious gathering was held in New London on Sept. 25.

Between the two conventions, it took 898 separate ballots to nominate compromise candidate John Hutton, an Audrain County doctor and attorney.

“It was the least expected of any political event that could happen,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat proclaimed.

Hutton even sounded stunned. “I need not say I expected this nomination,” he said. “I might say I did not expect it, knowing that circumstances were largely against me in the district.”

Opponents claimed Hutton had visited only four of the district’s counties – a big-time blunder in The Bloody Seventh. Many Democrats saw the 56-year-old Tennessee native, Union Civil War veteran and newspaper publisher “as the damnation of their hopes of success,” according to the Globe-Democrat. Without offering an alternative, it described him as “wholly unfit” and “entirely too uncertain to be useful.”

Hutton’s paper, The Weekly Intelligencer, unsurprisingly barked back, saying he had “stood as a leader, as a giant, in the fight for Democratic supremacy” and had “always had the harness on.”

Meanwhile, Republicans were joyous. If anyone could beat a concession Democrat in an area where the GOP had been shut out since the end of the Civil War, it was Matthew Reynolds.

The 29-year-old Naval Academy graduate, state legislator and Louisiana attorney was a law partner of former Missouri Supreme Court Justice Thomas James Clark Fagg. It didn’t hurt that he’d married the judge’s daughter, Maime.

Born in Bowling Green, Reynolds was the son of a doctor. A grandfather had stayed in America after serving as a surgeon with the British during the War of 1812.

Smart, capable, handsome and with a brood that would eventually grow to seven children, Reynolds was the ideal office-seeker.

Three days before the general election, Republicans held a rally at Louisiana’s Burnett Opera House. Local attorney David Patterson Dyer gave what the Globe-Democrat called an “earnest and exhaustive” speech.

“He charged the Democratic party with being one of corruption and deceit; said that its platform was like a thing that worked at both ends without any meaning or purpose, save to mislead; a now-you-see-it-and-now-you-don’t-see-it sort of thing,” the paper said.

By then, Robinson was knee-deep in overseeing a murder trial, but urged his former supporters to back Hutton.

Horton was less benevolent. The Ledger said he was “beginning to think the whole thing cost more than it was worth” and the Globe-Democrat said he “had no tears as big as biscuits in his eyes.”

Robinson’s endorsement carried weight. Though he cut into the Democratic margin of victory in the 1884 election, Reynolds was defeated by 333 votes in Pike County and more than 1,700 district-wide in 1886.

Still, the Ledger offered a worrisome observation, saying the “majority of the Democratic party voted for Hutton rank and file because he was the nominee of the party, but independents and non-partisan voters who are under no such obligation let him severely alone.”

Next time: Calm before the storm?

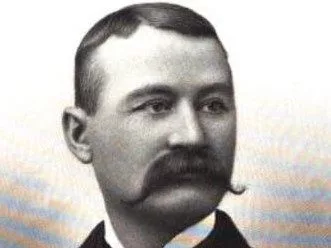

CUTLINE FOR PHOTO:

Matthew Reynolds