By Brent Engel, Contributing writer

Clark candidacy is national focus in May 1912

Champ Clark’s campaign to win the Democratic presidential nomination was chugging along in May 1912.

That it would come off the rails just two months later was something few would have believed possible.

The New York American called the Speaker of the House “the greatest and most effective fighting machine the Democratic party has ever known.” The Kansas City Times said he was “the most formidable candidate” in the race.

“Everything is coming Champ’s way right along,” the Mexico Ledger added.

“Champ Clark is like an old Atlas,” wrote the Ralls County Record. “He is carrying the earth.”

“If you do not believe that our own Missouri Champ Clark is slated as a winner, don’t try to think again,” the St. Joseph Observer chastised.

The Mokane Missourian printed a lengthy poem that included the lines “For 1912 to head the crew, are men of worth and mark, but for a captain wise and true, just try our own Champ Clark.”

Most tributes portrayed Clark as a common man who rose from humble roots.

“Champ Clark is a man without frills,” wrote journalist Arthur W. Dunn. “Each succeeding honor has found him unchanged.”

While the profile was accurate, some papers said Clark was now much more pretentious. The Poplar Bluff Republican dismissed the idea of the country’s third most powerful politician being humble after a “quarter-century of nursing at the public’s bottle,” and said his managers were making “a national beggar” of him.

“This ‘poor man’ plea is nauseating,” it said, adding that any man “too inefficient so to handle his own affairs” should never be put at “the head of the American government on the ungrounded supposition that he would run IT successfully.”

The Boston Herald declared that if Clark were to win the nomination, the election would “become a roaring burlesque.”

“The crazy things which he is not already on record as having said he would doubtless supply as the campaign advanced,” the Herald offered.

The New York Evening Sun said a vote for Clark would be “an eloquent exhibition of Democratic folly and assinity.”

The New York World made fun of the Speaker’s Missouri drawl, calling it “slang-whanging.”

The New York Globe predicted that neither Republican incumbent William Howard Taft nor challenger Theodore Roosevelt were electable. “Unless, of course, the Democrats nominate somebody like Champ Clark.”

Clark’s main rivals for the nomination were two governors, Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey and Judson Harmon of Ohio.

For his part, Clark kept making appearances while letting his campaign staff issue political statements. His speeches invariably focused upon issues facing America, not the personalities of his Democratic rivals.

“He is now nearer the Presidency than any Missourian has been since the days of Thomas Benton, and is about the only resident of the State who isn’t excited about it,” the Washington Herald joked.

The World claimed a Clark nomination “would mean Democratic suicide” because he wasn’t liberal enough and would not appeal to independent voters whom the party needed.

The paper predicted Clark would do worse in Eastern states than Nebraska Sen. William Jennings Bryan, the 1908 Democratic presidential candidate who got trounced.

Democrats apparently weren’t reading the World. Clark consistently beat Wilson and Harmon in a measure the party tried for the first time in 1912 – presidential primaries. Most state delegations pledged themselves to Clark.

“Champ Clark’s strength is growing in every part of the Union,” the Gallatin Democrat proclaimed. “

The American went so far as to compare Clark to a Republican hero.

“He is much of the type of (President Abraham) Lincoln,” the paper said. “Strong, rugged, homely, simple in manner, full of humor, great hearted and incorruptibly honest.”

If that wasn’t enough, things got bizarre when the widow of Kansas politician Jerry Simpson revealed she’d been communicating spiritually with her dead husband. She quoted him as saying Clark would be elected president and that he was “doing all I can for him.”

Even if help had come from beyond the grave, it would not have been enough to overcome a surge for Wilson at the Democratic National Convention in July. Bryan led efforts to draw support away from Clark.

Though the Speaker would later forgive the senator, his initial reaction was that he lost the nomination “solely through the vile and malicious slanders” made by Bryan.

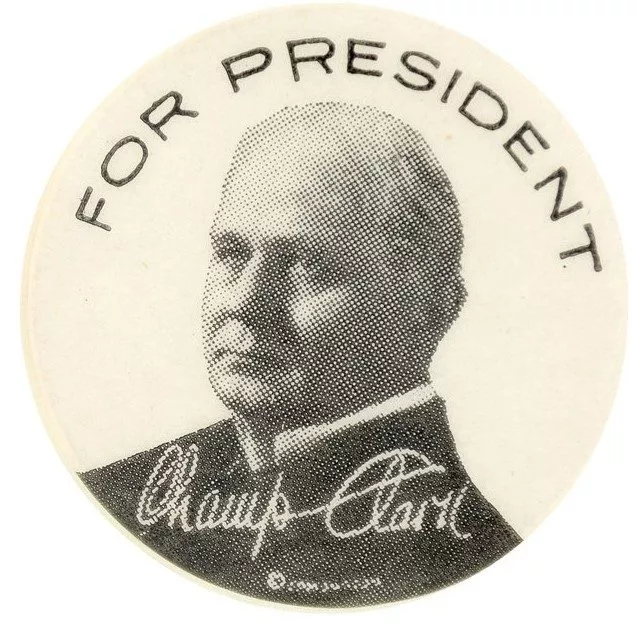

CUTLINE FOR PHOTO:

A 1912 “Champ Clark for President” button made by the Lucke Badge & Button Co. of Baltimore.