PIKE COUNTY, Mo. –He knew better, but put himself in danger to help his comrades.

Lt. Col. Pembroke Senteny of Pike County and the rest of the 2nd Missouri Confederate Infantry were pinned down as the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg raged. Union troops were hiding behind barriers as little as 50 feet away. The earthen barricade used by the rebels was so low that men had to reload guns while kneeling.

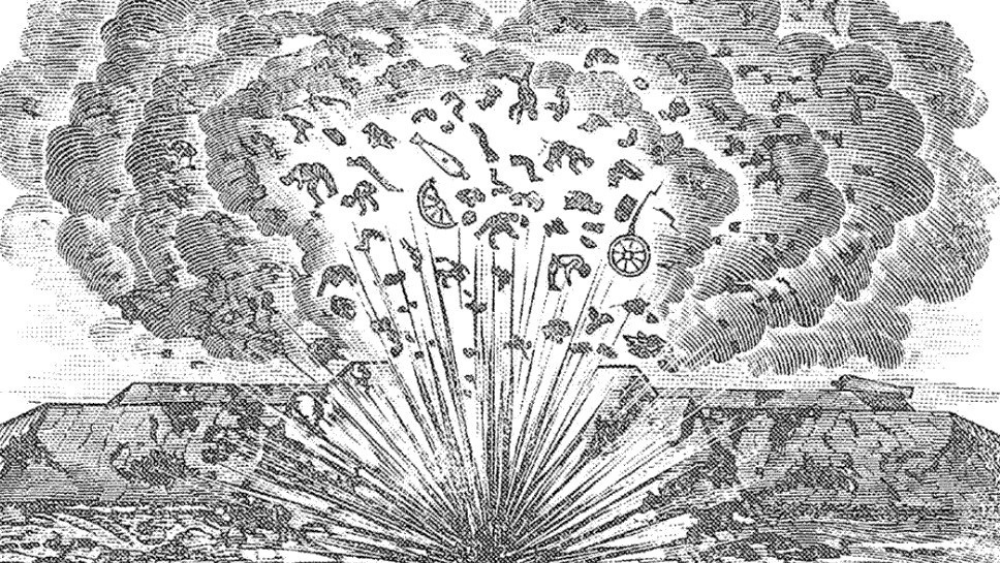

The federals had already blown up a deadly mine underneath the position and were working on a second.

In addition, they’d come up with an ingenious explosive made from small, hollowed logs that could easily be thrown into the Confederate line. The rebels were left with little to eat but mule meat.

Worst of all, a Union charge was expected at any moment. Confederate officers tried to quell fears. Brigade Commander Francis Cockrell had been blown into the air by the mine blast. Despite being wounded, he rallied the men.

“Forward, my brave old Second Missouri, and prepare to die!” Cockrell shouted.

Though not as boisterous, Senteny was just as vigilant and undeterred. An educator and store owner back home in Louisiana, he was considered a cautious commander who valued planning and reconnaissance.

As night fell on July 1, the colonel peered over the parapet to scout bluecoat positions. A vigilant sniper fired a shot that pierced Senteny’s skull. As his lifeless body fell backward, even battle-hardened men were left aghast.

“With bitter tears of grief and sorrow, the regiment beheld the body of this gallant officer, who had led them through many trying scenes and fiery ordeals, now borne back a corpse,” wrote Ephraim McDowell Anderson.

Named for a grandfather who was a pioneering doctor, Anderson was born in Tennessee but was living in Monroe County of Northeast Missouri at the outbreak of the war.

Anderson told how he remarkably had been kept from a similar fate as that of Senteny. While at Vicksburg, Anderson fired a shot at Union troops through a hole in the embankment and stepped aside to let another soldier shoot. The man got off a round, but pushed Anderson aside while insisting on firing again.

Anderson said a “ball passed through the aperture, and, striking him just below the eye, came out the back of his head, and he fell instantly dead.”

Anderson said Senteny’s men “loved him as their friend, and honored and esteemed him” as a commander.

“No more would we hear his calm and deliberate, though firm and quiet, commands, and be reassured and stimulated, in the hour of danger, by his self-possessed and determined bearing,” wrote Anderson, whose extraordinary autobiography, “Memoirs,” is available online.

Author Timothy B. Smith said confusion resulted from Senteny’s death and that the Union likely could have achieved a victory had a charge been made. While no assault happened, the Confederates surrendered three days later.

Senteny initially was buried near where he fell, but later was disinterred and brought to Riverview Cemetery in Louisiana. His wife, Fannie, a Confederate spy, is also buried there. Upon removal, his “uniform and boots, with spurs, were found in a nearly perfect condition,” one author wrote.

The Vicksburg National Military Park was established in 1899, and features more than 1,350 monuments to men and units on both sides. The memorial to Senteny was donated by Edwin Jefferson Bomer of Vicksburg and erected in June 1920. It cost what would today be almost $3,400.

There have been other tributes over the years. In 1939, the Journal of the American Military Institute said Senteny was “reputed to be one of the best field officers of his division.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy magazine said in 1989 that his name “will ring forever in the annals of southern military service.”

In the featured image; a graphic drawing shows a mine explosion along the Confederate line at the Siege of Vicksburg. The graphic is from the book “Memoirs” by Ephraim McDowell Anderson.