PIKE CO, Mo — John Brooks Henderson rarely spoke with such purpose as he did during bitter debate about the 14th Amendment in the summer of 1866.

The Missouri U.S. Senator and Pike County attorney had drafted and introduced the amendment that ended slavery. So, guaranteeing additional freedoms came naturally.

“Under all the circumstances, I think the country should accept the amendment, for it does much toward settling some of the vexed questions of the past,” Henderson said.

The amendment dealt with citizenship and equal application of the laws. While it was a huge advance for individual liberties, it was the nail in coffin for states’ rights. Henderson liked the overall concept and understood the intentions, but brought up a few points.

First, he argued the Constitution had already recognized citizenship at the time of its ratification 75 years earlier.

“It cannot be otherwise than that all free natural-born residents of the States and all who had been naturalized by the States became, at the adoption of the Constitution, citizens of the United States,” he said. “Their descendants, of course, followed their condition. All born of such parents became citizens at their birth.”

Second, Henderson claimed the amendment “separates representation from taxation,” but clearly liked that states which messed with voting rights could face punishment. Many Democrats who had controlled Southern legislatures before the Civil War were stepping back into leadership positions. In addition, the South was about to get more representatives in Congress because blacks would be fully counted.

“The States under the former proposition might have excluded (blacks) under an educational test and yet retained their power in Congress,” he said. “Under this, they cannot.”

A third point addressed a section of the amendment that banned anyone from holding most elected offices if they’d “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against” federal or state governments and those who had “given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

“We cannot punish all,” Henderson noted. “To discriminate among those who are equally guilty wears the garb of injustice.”

Henderson added that illegal punishment would be a form of depriving people of life and liberty, two of the principles highlighted in the first section of the amendment.

“These are absolute or inalienable rights,” he said. “To take them away is an injury to the person. They ought never to be taken away without due process of law.”

The fourth section of the amendment voided debts from the war and said the federal and state governments had no obligation to pay the bills of those who rebelled against them.

“No agreement founded on an immoral consideration, no contract made, the object of which is to resist the law or overthrow the Government, can be enforced,” Henderson said.

Illinois endorsed the Amendment on Jan. 15, 1867, and Missouri followed 10 days later. Despite efforts at compromise, the South hated the proposal. Every former Confederate legislature except that of Tennessee refused to accept it.

In response, Congress passed four laws over the next two years that set up military governments in the South, required states there to pass the 14th Amendment and draft new constitutions that met with Washington’s approval

Secretary of State William Seward certified the amendment as part of the Constitution when South Carolina – where the war had started – accepted it on July 9, 1868. Nine states would do so after that date. Kentucky waited almost 110 years, finally ratifying on March 30, 1976.

The amendment has regularly sparked controversy on a wide spectrum of issues. Henderson offered a suggestion that, perhaps, would apply.

“Why cannot gentlemen rise above the trammels of party influences and do what they feel within their souls and consciences to be correct action?”

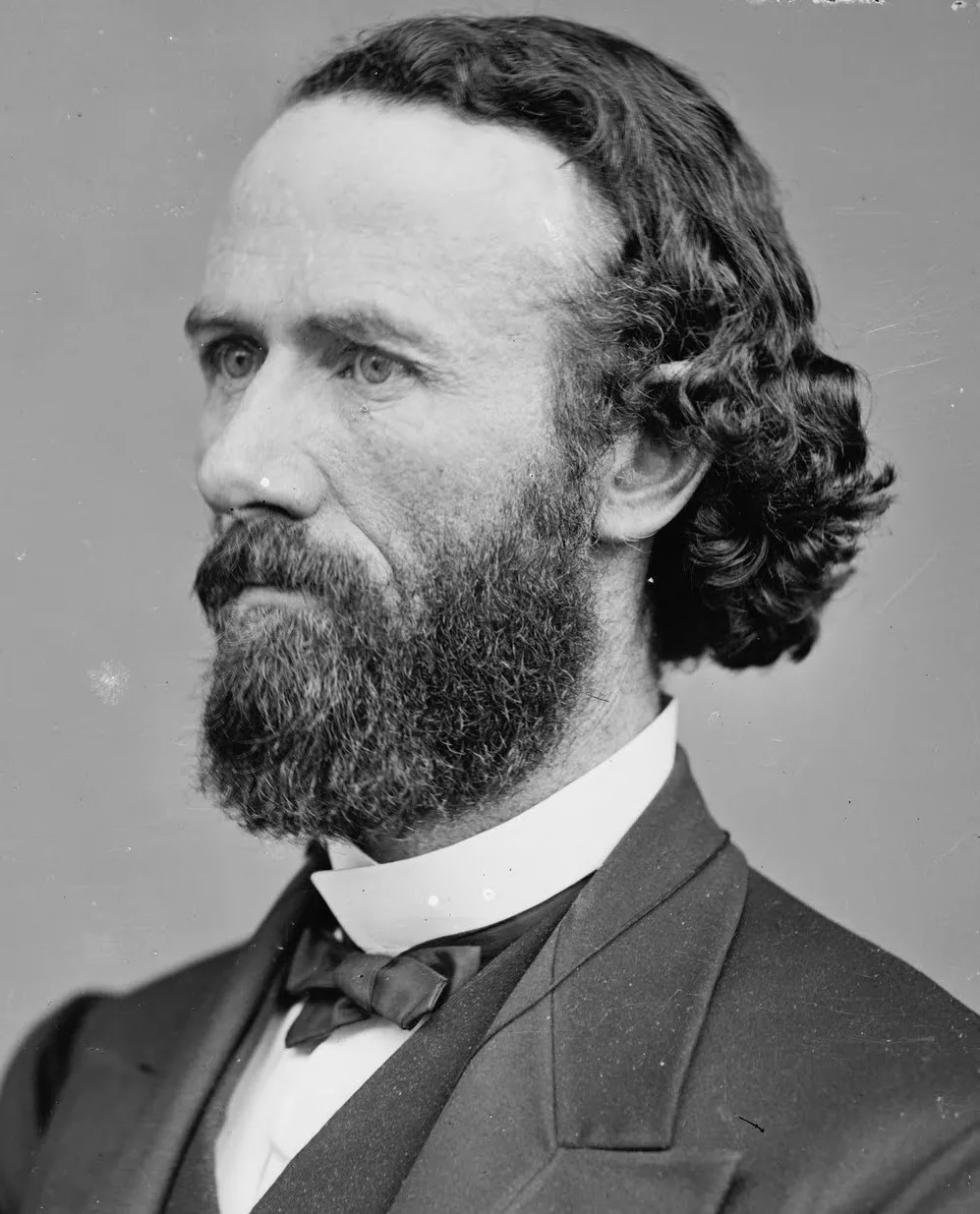

CUTLINE: John Brooks Henderson