BOWLING GREEN, Mo. — By Brent Engel, Contributing writer.

He was enterprising, talented and principled.

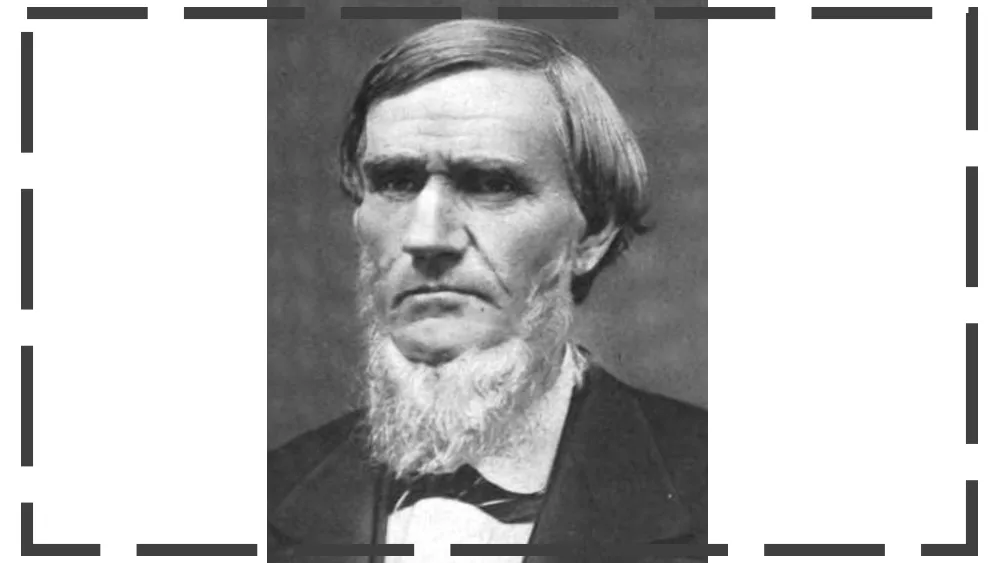

William Gordon Hawkins was the kind of guy just about everyone probably wishes they had in the family.

The life of the Bowling Green man, who got the nickname “Uncle Billy” for his patriarchal persona, offers the kind of lessons that resound today.

“The best qualities of American manhood met in him, and the Christian graces elevated his character,” noted the Rev. Wiley Jones Patrick, author of “The History of Salt River Association, Missouri.”

Southern-born

Hawkins was born in Kentucky on Feb. 26, 1809, the youngest of Harmon and Jane Robinson Hawkins’ three children.

His father was a farmer and a Baptist deacon. The family moved to Pike County in 1827. By that time, Hawkins had already shown a flair for ingenuity, such as when he trapped and sold quail to buy school books.

While the classroom was not a favorite spot, Hawkins loved mathematics, from which came a frugality that “in a measure compensated him for the neglect of his other faculties,” according to the book “A History of Northeast Missouri.”

A fascination with politics led to opportunity in 1832, when Hawkins became the first elected assessor in Pike County. He clerked at a Frankford business and would later own a store while also holding the title of colonel in the Missouri militia.

In 1833, Mount Pisgah Baptist Church was organized in the Hawkins home. A new sanctuary soon was sought. Father and son built the church’s stone chimney and, with others from the congregation, erected a large log place of worship.

The cost was estimated at less than $20 – around $600 today. Patrick wrote that church members had “very little money for any purpose,” but “taken all together it was a pretty fine house for that age of the church and country.”

On July 26, 1836, Hawkins married Kentucky native Martha Bondurant, who was five years younger. They would have eight children.

Hawkins served as a sheriff’s deputy in the 1840s and held the top spot from 1852 to 1858. During that time, he also was elected as a Democrat to the Missouri House of Representatives.

“He exhibited certain traits betraying a latent gift for statesmanship,” the Missouri history book noted.

Martha died in 1854 and Hawkins married another Kentucky native on April 3, 1857. Mary Susan Givens Mackey was 18 years younger than her husband. The couple would have four children.

Confederate sympathies forced Hawkins out of office during the Civil War. One of his sons, Edward, was killed fighting for the South at the Battle of Corinth in October 1862. Another son, Richard, was captured by Union forces but released.

Holding no grudges, Pike County voters returned Hawkins to the Missouri General Assembly in 1872 and 1874.

As a reformist, he kept “his eye upon the finances of the state to such a pronounced extent to earn for him the well-remembered sobriquet of ‘Watchdog of the Treasury,’” according to the Missouri history book.

“He was in every way capable of making himself heard and understood while upon the floor of the House, and his popularity was widespread and universal,” it said.

Patrick called him a “legislator of experience, ability, with a love of his country and definite knowledge of the constructive needs” of Pike Countians.

‘Great and salutary’

Success in business and politics was one thing, but Hawkins also was interested in more divine pursuits.

He never forgot religious lessons of his younger days, and became a church deacon as his father had.

Patrick called Hawkins “one of nature’s noblemen” whose influence was “great and salutary.” It was as “a Christian gentleman and a Baptist leader that his powers found their fullest expression.”

The author noted that Hawkins was “held in high honor” for being among those who “rejoiced to tell how the gospel was the power of God unto salvation” and that countless people became believers because of his efforts.

“He was fervent and active in revival service; he was gentle and sympathetic with the afflicted; he was beneficent toward the needy; efficient in the Sunday School; strong in the business departments of church life; and a recognized representative in denominational movements,” Patrick wrote.

“He was noted among his peers as a safe, conservative, prudent man whom all could approach for advice with confidence – with assurance of wise counsel,” said a friend, Dalton Biggs.

One of Hawkins’ traits was an “ability to avert a pending disturbance,” according to Biggs. He relayed how Hawkins calmed a divisive church association meeting that “reached the point where an explosion seemed unavoidable.”

Using his height and assertive presence as he stood before other brethren, Hawkins called for the issue to be “laid on the table, and left there for time and eternity to settle.”

“It was a master stroke,” Biggs said. “That matter still rests, where by his wisdom it was placed, and there it doubtless will remain until settled in the day of final accounts.”

Despite age, Hawkins maintained his connection to the family farm, often walking the spread of more than 500 acres or visiting neighbors. His legacy as sheriff continued when a son, Waldo, served in the office from 1913 to 1916.

Hawkins died at 79 on Jan. 12, 1889. Mary followed at 65 on July 23, 1892. He and both spouses are buried at Mount Pisgah Cemetery northwest of Bowling Green.

“Of all those whose memory we cherish, perhaps none enjoyed a more enviable life or a longer term of usefulness than Col. W.G. Hawkins,” Biggs noted.