PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — Fate has denied Pike County two presidents.

Much attention has been focused upon party infighting that kept Bowling Green attorney Champ Clark from winning the 1912 Democratic nomination.

The spotlight has not shown as brightly on the 1940 U.S. Senate Democratic primary. It pitted Louisiana nursery owner Lloyd Stark against incumbent Harry Truman, who became vice president and ascended upon the death of President Franklin Roosevelt.

The passage of time makes lack of attention understandable. Yet, intrigue was created by the bitter race, which would see another Pike County influencer make his mark.

If nothing else, the campaign solidified Truman’s sometimes coarse persona while proving the old adage that politics makes for strange bedfellows. It all came amid a backdrop of a war in Europe and Asia that soon would draw in America.

Truman recounted a 1939 meeting he had in his Washington office with Stark, who promised not to challenge the senator.

“When he left my office, I said to my secretary ‘That son-of-a- ____ is gonna run against me, and, sure enough. I was right,” Truman later said.

Gigantic loathing

Stark and Truman despised each other, and the 1940 race would make them enemies for life.

Just four years earlier, however, they’d been buddies. Stark said Truman was “one of the best friends I have in the world.” Truman pledged that if he could “be of any service in any way whatever, all you need to do is indicate it, and I will be there.”

Hostility erupted with the downfall of crooked Kansas City political boss Tom Pendergast. Truman had received campaign help from Pendergast in his 1934 Senate bid. Stark had been rebuffed by the powerbroker in the 1932 gubernatorial race, but received reluctant support in 1936.

When charges of corruption arose, Truman stuck by Pendergast despite not being part of the fraud. Stark championed the investigations.

“The decent, honest, law-abiding, God-fearing people of Missouri – you and countless thousands like you – deserve the full credit for ridding our state of the domination of a greedy, rapacious gang of plunderers and corruptionists,” Stark told one audience.

By 1939, Pendergast was in prison, Truman was questioning his re-election chances and Stark was basking in the national spotlight, including attention from the White House and a favorable five-page spread in Life magazine.

Stark filed as a candidate on Sept. 15, 1939. Two weeks earlier, the Nazis had invaded Poland. In Louisiana, handbags could be purchased at Younkers department store for 50 cents, three pounds of green beans were 30 cents at Sterne Market and “The Invisible Man” was one of the features at the Clark Theatre.

Truman finally announced his candidacy on Feb. 3, 1940. Three months later, Stark held a formal campaign kickoff. A grandstand roof kept rain off of an estimated 5,000 spectators as Stark spoke from a makeshift covered podium built on the racetrack at the Audrain County Fairgrounds in Mexico. The governor spoke for 45 minutes and afterward greeted the audience for an hour.

The candidate said he was “unalterably opposed” to America joining overseas wars and advocated a “defense only” policy.

“We need our young people to work out the peaceful problems of tomorrow and to maintain in this nation the high idealism upon which democracy thrives,” he said.

An inspirational finish to the speech, with an eye toward the end of the Great Depression, drew loud applause.

“The years ahead that call for the solution of fundamental problems in agriculture, business and labor will reward those who solve those problems by justifying their faith in America,” Stark said. “The solution of those problems will re-employ our people beyond the need of expedients or relief or of created work.”

Different drummers

Stark was more conservative than Truman.

The man from Independence was an intelligent, yet scrappy, farm boy who loved music and reading. He relished persevering amid troubles, and any self-doubt was overcome by persistence.

“My choice early in life was either to be a piano player in a whorehouse or a politician,” he once joked. “And to tell the truth, there’s hardly any difference.”

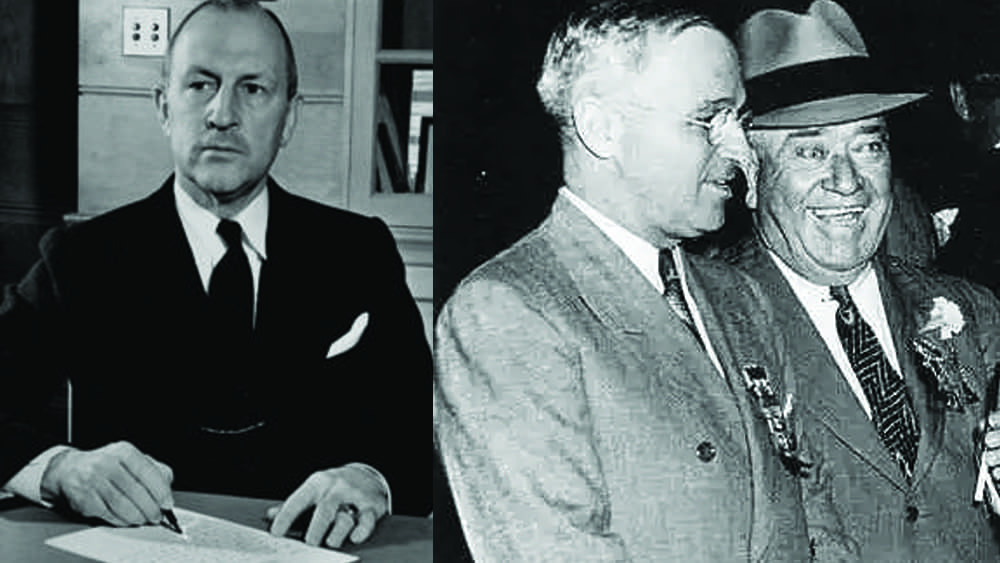

Stark was about as opposite as could be – the kind of successful, dignified gentleman hardly ever found in politics. He was poker-faced and personally reserved, but magnanimous and deeply passionate about progress.

Before entering politics, Stark had galvanized efforts to build the Champ Clark Bridge at Louisiana. In addition to breeding blue-ribbon horses, he advocated unambiguous government and denounced partisan parasites who considered “public office as a private racket.”

Voters also got a reminder that democracy came with responsibility. “Good government begins with your ballot,” he once told a Rotary Club audience.

Critics called Stark a rich egomaniac whose thirst for power was unquenchable. Washington columnist Jay Franklin wrote that the governor had “a stiff and pompous official manner, which is a political handicap.” Author Robert H. Ferrell said Stark was “an ingrate” for turning on Pendergast and for not acknowledging Truman’s support of his gubernatorial candidacy.

Those backing Stark labeled Truman an unimpressive legislator who was little more than the puppet of a rotten political scoundrel. Capitol reporters Joseph Alsop and Robert Kintner said he was “an appendage of the old Pendergast machine.” The senator admitted he was “under a cloud.”

In diary entries, Truman criticized Stark as a “double crosser” who was “intellectually dishonest.” He claimed the Louisiana businessman had “followed me around like a poodle dog” to gain support in the 1936 governor’s race. Truman would later say that Roosevelt had told him Stark had a “large ego” and “no sense of humor,” and that the governor was not “a real liberal.”

Friends had urged Truman not to seek office again. Roosevelt appeared to quietly back Stark, and apparently promised Truman a lifetime Interstate Commerce Commission appointment at a higher salary if he quit the race.

“I sent word that I would run if I only got one vote – mine,” a typically defiant Truman reportedly told an aide.

Lloyd Stark wasted little time in attacking Harry Truman in their 1940 campaign for the Democratic U.S. Senate nomination.

The term-limited Missouri governor called the incumbent a “fraudulent” hack elected with “ghost votes” provided by Tom Pendergast’s Kansas City political operatives. He promised “clean, honest government” if elected.

“I am proud of the part the good people of this state played in the cleanup of the Pendergast machine,” Stark said. “Without their influence, the battle for decent government in Missouri might never have succeeded.”

Most newspapers favored Stark. The New York Times called Truman “a rube from Pendergast land” and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch predicted his political days were over.

“He may as well fold up and accept a nice, lucrative federal post if he can get it – and if he does get it, it’s a travesty of democracy,” the paper intoned.

- Gould Lincoln of the Washington Evening Star said Stark “is the kind of man needed in American politics.” As he had so many times, Truman offered a quintessential comeback when asked about his opponent.

“I’ll beat the hell out of him.”

Flies in the ointment

Truman wasn’t the only man upset that Stark took credit for Pendergast’s downfall.

As U.S. District Attorney for Western Missouri, Maurice Milligan had put in prison the boss and more than 200 of his lackeys.

Truman, who six years earlier had received political help from Pendergast, unsurprisingly opposed Milligan’s appointment as a prosecutor. There also was an old-fashioned revenge factor. Truman had defeated Milligan’s brother, Jacob, in the 1934 Senate primary. Milligan began his own Senate run with promise on March 28, 1940.

All three candidates supported Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, although Truman was more outspoken and consistently voted with the president. The trio also hoped to keep America out of escalating wars in Europe and Asia.

The problematic commonality between Truman and Stark was Bennett Clark, Missouri’s other U.S. Senator and son of the late Pike County legislator Champ Clark. He didn’t like Stark and was barely tolerable of Truman.

Clark had stunned political watchers by winning his seat in 1932 without Pendergast’s support. His animus toward Truman dated to the 1934 Senate primary, when Clark had backed Jacob Milligan.

Though they seemed to get along in the Senate, Clark had excoriated Truman for “mendacity and imbecility.” In yet another typical response, Truman said Clark was proof that talent wasn’t inherited.

Like his father, Clark was a loyal Democrat. He generally supported Roosevelt, even serving as the president’s chief 1936 re-election campaigner in Missouri. However, author Thomas T. Spencer noted the senator “did not hesitate to vote against New Deal legislation that he opposed on principle or considered unconstitutional.”

Stark picked up on the negative vibes and made sure voters understood his support of Roosevelt.

“This is a dangerous time, and is no time for partisan and carping criticism at the man at the helm of their government, who has at his hands the destiny of every man, woman and child in the United States,” Stark said.

It also was a time of one big question. For as Democrats approached the party’s national convention at Chicago in July, Roosevelt still had not revealed whether he planned to seek an unprecedented third term.

Clark quickly found himself on a long list of possible candidates.

Cold shoulder

Truman had long felt ignored by Roosevelt.

He had gotten little attention during six years in the Senate and he’d even been left to sulk on shore while Stark sailed the Potomac aboard Roosevelt’s yacht.

So, Truman initially backed Clark for president in 1940. In hindsight, observers have differed on if it was a shrewd or senseless decision.

Author Thomas Fleming claimed Truman’s support was the kind of ingenious “pure politics” that Truman cherished – an effort to attract votes in Clark’s Northeast Missouri backyard.

Author David McCullough countered by writing that it “seemed so blatantly hypocritical and expedient as to be laughable” that Truman would back Clark “for the presidency at any time, let alone now, with the world as it was.” Despite his endorsement, Truman said he would campaign for Roosevelt if the president decided to run again.

In addition to Clark, there were more than a dozen potential nominees. Newspaper columnist Jay Franklin called Clark “thoroughly honest” and “one of the real scholars” in Washington, but added that his “political company has been poorly chosen” and that he was part of “the conservative clique in the Senate which invariably opposes Roosevelt.”

Nicholas Wapshott wrote that Clark was among “the passing flavors of the month” and had no real shot at the nomination. McCullough was much harsher, and said no one was surprised when Clark’s “presidential boom came to nothing.”

It didn’t help that Stark was openly hostile to Clark, even though Champ had been a teacher of the governor’s father, Clarence, and had given the younger man an appointment to the Naval Academy. Only four years apart in age, the two men had known each other since childhood.

The Associated Press reported that Clark’s vitriol toward the governor had “earned for him the title of No. 1 Stark-hater” and that the senator’s “prime interest was to see Stark beaten.”

Stark ignored the jabs and kept on campaigning, splitting his time between Missouri and Washington, D.C. Milligan sought Pike County votes by advertising in Stark’s hometown newspaper, The Louisiana Press-Journal.

Truman did what had worked for him previously. He hopped into his 1938 Dodge and blitzed the state, visiting every burg he could – 75 counties in June and July alone. Bess Truman often reworked his speeches to avoid her husband’s sometimes gruff descriptions. At one rally, Truman’s address included multiple uses of the word “manure.”

“Why on earth can’t you get Harry to use a more genteel word?” a friend asked.

“Good Lord, it’s taken me years to get him to use ‘manure,’” Mrs. Truman replied.

Meanwhile, at Bowling Green High School, a senior named William Hungate was keeping one eye on the war overseas and the other on the Senate race.

Later, the Army combat veteran and Missouri Congressman would make a hindsight observation about the ineffective vandalism that hit Truman’s campaign in Stark territory.

“As fast as you took down his posters, someone else put them up,” Hungate recalled. “He was recognized across the state as a champion of the people.”

Thus, the stage was set for a remarkable election.

The road to defeat for Lloyd Stark may have been lined with fruit from his Louisiana orchards.

Stark narrowly lost the 1940 Missouri U.S. Senate Democratic primary election to incumbent Harry Truman in a race that also featured Maurice Milligan.

There were at least two significant reasons, but a more intangible theory left a bad taste that would damage Stark.

It happened during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago just three weeks before the primary. While President Franklin Roosevelt had decided to seek a third term, there was uncertainty over who would join him as vice president. The first man to hold that title, John Nance Garner, was challenging Roosevelt for the presidential nomination.

Stark, Missouri’s term-limited governor and a delegate to the convention, handed out apples at Chicago Stadium and let everyone know he would gladly be Roosevelt’s running mate.

“I’m going to let nature take its course,” he coyly told reporters. “I’m not announcing as a candidate, but I told the boys I’m not going to hold them back any longer.”

Boiling point

Handouts are synonymous with politics, so Stark’s amiable antic was nothing new.

The trouble came from a man whom the governor had known since before he could pick fruit.

Bennett Clark, Missouri’s other U.S. Senator and the son of former Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Bowling Green, did not see eye-to-eye with Stark.

When Stark had first been mentioned for vice president in February 1940, Clark sarcastically responded that his fellow Pike Countian’s “ambitions seem to be like the gentle dew that falls from heaven and covers everything high or low.”

“He is the first man in the history of the United States who has ever tried to run for President, Vice President, Secretary of the Navy, Secretary of War, Governor General of the Philippines, Ambassador to England and United States Senate all at one and the same time,” Clark growled.

The Associated Press reported the “gap between those two sons of Pike County widened steadily” during the Missouri Democratic Convention in April. Clark’s animus paid off for Truman, who was warmly received by delegates at the national convention. Despite the apples, Stark was booed.

On the flip side, the St. Louis Star-Times criticized Clark for his “extreme verbal assaults on the governor” and argued that the senator should have supported Stark’s anti-corruption efforts.

Clark called Stark’s attempt to join the Roosevelt ticket “a ludicrous fiasco.” Stark responded by saying Clark was jealous that national attention had shifted away from the senator’s own aspirations for higher office.

“Missourians know that I have been, and am now, an ardent supporter of President Roosevelt,” he said. “Senator Clark sees red when my name is mentioned.”

Stark soon decided to withdraw from the vice president balloting, but “a good many potential supporters from Missouri felt that he had made a fool of himself and of them by running for two offices at the same time,” wrote author Merle Miller.

The Jefferson City Post-Tribune said Stark’s escapade “cost him prestige at home,” and that it would take time for his reputation to rebound from “all those apples given away for free.”

In the end, Roosevelt chose Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace of Iowa. Truman, Stark and Milligan differed little on issues, especially in keeping America out of conflicts in Europe and Asia.

So, the race came down to good, old-fashioned handshake campaigning – something at which Truman excelled.

Enemy of my enemy

During World War I, Truman had encountered Clark on a European battlefield.

The future senator convinced the future president that a German attack was about to happen. It didn’t, but Truman wisely did not hold a grudge for the practical joke. Clark would help his 1940 campaign immeasurably.

Clark was among those who had encouraged Milligan to join the race. Truman admitted the prosecutor was “riding a wave of popularity” after winning convictions of Kansas City political kingpin Tom Pendergast and his cronies.

Truman fell back upon what had worked in his 1934 Senate race. He drove around the state to rallies and speeches, getting reacquainted with people he’d met six years earlier. His wife, Bess, and 87-year-old mother, Martha, joined him at many stops.

Stark, a Naval Academy graduate who had served with distinction during the war, began to feel the heat. Days before the Aug. 6 election, a letter went out to supporters.

“Be active!” he wrote. “Be vigilant! Our chief danger is over-confidence. Beware of the friend who tells you ‘It’s in the bag. Stark is as good as nominated. Your help is not needed.’ Remember, one vote in the ballot box is worth a dozen on the street corner.”

Truman went to bed on election night trailing Stark by 11,000 votes. Thinking the call was a joke, Bess hung up on a campaign aide who rang at 3:30 the next morning to say Truman had pulled ahead.

In the end, the senator received 268,354 votes to Stark’s 260,221 – a difference of only 8,133. Milligan had 127,378. To no one’s surprise, Stark easily came out on top in Pike County, with 3,482 votes to Truman’s 1,184. Milligan got 758.

Analysts theorized Milligan siphoned votes from Stark. In addition, Truman got an overwhelming majority of the 130,000 votes cast by black people, a constituency Stark and Milligan largely ignored.

Truman “pulled off a minor miracle,” wrote Robert Dallek. Biographer Rawn James Jr. said “colleagues, opponents and pundits repeatedly underestimated” the senator.

Stark’s disposition did not allow excuses, and he largely was quiet about the defeat. While offering to campaign for Roosevelt, he refused to support Truman, who beat Republican Manvel Davis by more than 50,000 votes in the November 1940 general election.

Truman told Bess that he would not forget the primary if he lived to be 1,000.

“I hope some good fact-finder will make a record of that campaign,” he said. “It will be history someday.”

Aftermath

Even in victory, Truman did not hold back his feelings about Stark.

In a letter two weeks after the primary, the senator told a friend of the nursery owner that he “didn’t want to hear from the S.O.B.” and “didn’t give a damn what he did or intended to do.”

Truman would later say that the only person he detested more was Republican Richard Nixon, whom he called “a no good, lying bastard.” That didn’t stop him from excoriating Clark, whom he claimed “was never any help as a representative of the people of Missouri” during Roosevelt’s tenure.

Clark was part of the controversy over Stark’s successor as governor. He and others charged that Republican Forrest Donnell had won the election with fraudulent votes and demanded a recount.

Donnell was kept out of office for six weeks until the Missouri Supreme Court stepped in to seat him. Newspapers ran a photo of Donnell and a smiling Stark greeting each other.

There is, of course, no guarantee that Roosevelt would have chosen Stark as his running mate after dumping Wallace in 1944. But there’s no doubt the Pike County man would have been a viable leader.

Speculation ramps up even more when considering what might have happened if Stark had beaten Truman. At the least, two men from Pike County who detested each other would have represented Missouri in the Senate, all the while likely seeking a higher office. The intrigue multiplies when thinking of Stark – considered by many more exceptional than Clark – being elevated to president.

In any event, Stark returned to the nursery business and never ran for political office again. He did back Republicans such as Thomas Dewey, whom Truman defeated for president in 1948. Stark died at 85 on Sept. 17, 1972.

Clark continued in the Senate and introduced the G.I. Bill, among other successes. Showing no apparent ill will, Truman nominated him as a federal judge, a position Clark held until his death at 64 on July 10, 1954.

Milligan resumed his duties as a federal prosecutor and wrote a book. Its title – “Missouri Waltz: The Inside Story of the Pendergast Machine by the Man Who Smashed It” – proclaimed his role in bringing down the boss. He passed at 74 on June 19, 1959.

Truman had been vice president for less than three months when Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. During World War II, he appointed Stark’s brother, Paul, to run a victory garden campaign. But there was never a loss of disdain for his 1940 rival.

Truman called Stark “a nut” who in 1940 “couldn’t make up his mind what he wanted to be, and then he tried to run for everything at the same time.”

One last thing

Missouri Congressman William Hungate had a fitting tribute to Truman upon the president’s death at 88 on Dec. 26, 1972 – just three months after Stark passed.

Hungate, who orchestrated preservation of Champ Clark’s historic Bowling Green home, related the story to colleagues in the U.S. House.

“Someone is alleged to have run up to Mr. Truman when he was running for Senate and said: ‘I bet you don’t know who I am.’ To which Mr. Truman said: “No, and I don’t give a damn.’ Well, a lot of us wish we could have that courage, but few of us could be elected doing that, except a man like Harry Truman.”

The road to defeat for Lloyd Stark may have been lined with fruit from his Louisiana orchards.

Stark narrowly lost the 1940 Missouri U.S. Senate Democratic primary election to incumbent Harry Truman in a race that also featured Maurice Milligan.

There were at least two significant reasons, but a more intangible theory left a bad taste that would damage Stark.

It happened during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago just three weeks before the primary. While President Franklin Roosevelt had decided to seek a third term, there was uncertainty over who would join him as vice president. The first man to hold that title, John Nance Garner, was challenging Roosevelt for the presidential nomination.

Stark, Missouri’s term-limited governor and a delegate to the convention, handed out apples at Chicago Stadium and let everyone know he would gladly be Roosevelt’s running mate.

“I’m going to let nature take its course,” he coyly told reporters. “I’m not announcing as a candidate, but I told the boys I’m not going to hold them back any longer.”

Boiling point

Handouts are synonymous with politics, so Stark’s amiable antic was nothing new.

The trouble came from a man whom the governor had known since before he could pick fruit.

Bennett Clark, Missouri’s other U.S. Senator and the son of former Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Bowling Green, did not see eye-to-eye with Stark.

When Stark had first been mentioned for vice president in February 1940, Clark sarcastically responded that his fellow Pike Countian’s “ambitions seem to be like the gentle dew that falls from heaven and covers everything high or low.”

“He is the first man in the history of the United States who has ever tried to run for President, Vice President, Secretary of the Navy, Secretary of War, Governor General of the Philippines, Ambassador to England and United States Senate all at one and the same time,” Clark growled.

The Associated Press reported the “gap between those two sons of Pike County widened steadily” during the Missouri Democratic Convention in April. Clark’s animus paid off for Truman, who was warmly received by delegates at the national convention. Despite the apples, Stark was booed.

On the flip side, the St. Louis Star-Times criticized Clark for his “extreme verbal assaults on the governor” and argued that the senator should have supported Stark’s anti-corruption efforts.

Clark called Stark’s attempt to join the Roosevelt ticket “a ludicrous fiasco.” Stark responded by saying Clark was jealous that national attention had shifted away from the senator’s own aspirations for higher office.

“Missourians know that I have been, and am now, an ardent supporter of President Roosevelt,” he said. “Senator Clark sees red when my name is mentioned.”

Stark soon decided to withdraw from the vice president balloting, but “a good many potential supporters from Missouri felt that he had made a fool of himself and of them by running for two offices at the same time,” wrote author Merle Miller.

The Jefferson City Post-Tribune said Stark’s escapade “cost him prestige at home,” and that it would take time for his reputation to rebound from “all those apples given away for free.”

In the end, Roosevelt chose Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace of Iowa. Truman, Stark and Milligan differed little on issues, especially in keeping America out of conflicts in Europe and Asia.

So, the race came down to good, old-fashioned handshake campaigning – something at which Truman excelled.

Enemy of my enemy

During World War I, Truman had encountered Clark on a European battlefield.

The future senator convinced the future president that a German attack was about to happen. It didn’t, but Truman wisely did not hold a grudge for the practical joke. Clark would help his 1940 campaign immeasurably.

Clark was among those who had encouraged Milligan to join the race. Truman admitted the prosecutor was “riding a wave of popularity” after winning convictions of Kansas City political kingpin Tom Pendergast and his cronies.

Truman fell back upon what had worked in his 1934 Senate race. He drove around the state to rallies and speeches, getting reacquainted with people he’d met six years earlier. His wife, Bess, and 87-year-old mother, Martha, joined him at many stops.

Stark, a Naval Academy graduate who had served with distinction during the war, began to feel the heat. Days before the Aug. 6 election, a letter went out to supporters.

“Be active!” he wrote. “Be vigilant! Our chief danger is over-confidence. Beware of the friend who tells you ‘It’s in the bag. Stark is as good as nominated. Your help is not needed.’ Remember, one vote in the ballot box is worth a dozen on the street corner.”

Truman went to bed on election night trailing Stark by 11,000 votes. Thinking the call was a joke, Bess hung up on a campaign aide who rang at 3:30 the next morning to say Truman had pulled ahead.

In the end, the senator received 268,354 votes to Stark’s 260,221 – a difference of only 8,133. Milligan had 127,378. To no one’s surprise, Stark easily came out on top in Pike County, with 3,482 votes to Truman’s 1,184. Milligan got 758.

Analysts theorized Milligan siphoned votes from Stark. In addition, Truman got an overwhelming majority of the 130,000 votes cast by black people, a constituency Stark and Milligan largely ignored.

Truman “pulled off a minor miracle,” wrote Robert Dallek. Biographer Rawn James Jr. said “colleagues, opponents and pundits repeatedly underestimated” the senator.

Stark’s disposition did not allow excuses, and he largely was quiet about the defeat. While offering to campaign for Roosevelt, he refused to support Truman, who beat Republican Manvel Davis by more than 50,000 votes in the November 1940 general election.

Truman told Bess that he would not forget the primary if he lived to be 1,000.

“I hope some good fact-finder will make a record of that campaign,” he said. “It will be history someday.”

Aftermath

Even in victory, Truman did not hold back his feelings about Stark.

In a letter two weeks after the primary, the senator told a friend of the nursery owner that he “didn’t want to hear from the S.O.B.” and “didn’t give a damn what he did or intended to do.”

Truman would later say that the only person he detested more was Republican Richard Nixon, whom he called “a no good, lying bastard.” That didn’t stop him from excoriating Clark, whom he claimed “was never any help as a representative of the people of Missouri” during Roosevelt’s tenure.

Clark was part of the controversy over Stark’s successor as governor. He and others charged that Republican Forrest Donnell had won the election with fraudulent votes and demanded a recount.

Donnell was kept out of office for six weeks until the Missouri Supreme Court stepped in to seat him. Newspapers ran a photo of Donnell and a smiling Stark greeting each other.

There is, of course, no guarantee that Roosevelt would have chosen Stark as his running mate after dumping Wallace in 1944. But there’s no doubt the Pike County man would have been a viable leader.

Speculation ramps up even more when considering what might have happened if Stark had beaten Truman. At the least, two men from Pike County who detested each other would have represented Missouri in the Senate, all the while likely seeking a higher office. The intrigue multiplies when thinking of Stark – considered by many more exceptional than Clark – being elevated to president.

In any event, Stark returned to the nursery business and never ran for political office again. He did back Republicans such as Thomas Dewey, whom Truman defeated for president in 1948. Stark died at 85 on Sept. 17, 1972.

Clark continued in the Senate and introduced the G.I. Bill, among other successes. Showing no apparent ill will, Truman nominated him as a federal judge, a position Clark held until his death at 64 on July 10, 1954.

Milligan resumed his duties as a federal prosecutor and wrote a book. Its title – “Missouri Waltz: The Inside Story of the Pendergast Machine by the Man Who Smashed It” – proclaimed his role in bringing down the boss. He passed at 74 on June 19, 1959.

Truman had been vice president for less than three months when Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. During World War II, he appointed Stark’s brother, Paul, to run a victory garden campaign. But there was never a loss of disdain for his 1940 rival.

Truman called Stark “a nut” who in 1940 “couldn’t make up his mind what he wanted to be, and then he tried to run for everything at the same time.”

One last thing

Missouri Congressman William Hungate had a fitting tribute to Truman upon the president’s death at 88 on Dec. 26, 1972 – just three months after Stark passed.

Hungate, who orchestrated preservation of Champ Clark’s historic Bowling Green home, related the story to colleagues in the U.S. House.

“Someone is alleged to have run up to Mr. Truman when he was running for Senate and said: ‘I bet you don’t know who I am.’ To which Mr. Truman said: “No, and I don’t give a damn.’ Well, a lot of us wish we could have that courage, but few of us could be elected doing that, except a man like Harry Truman.”