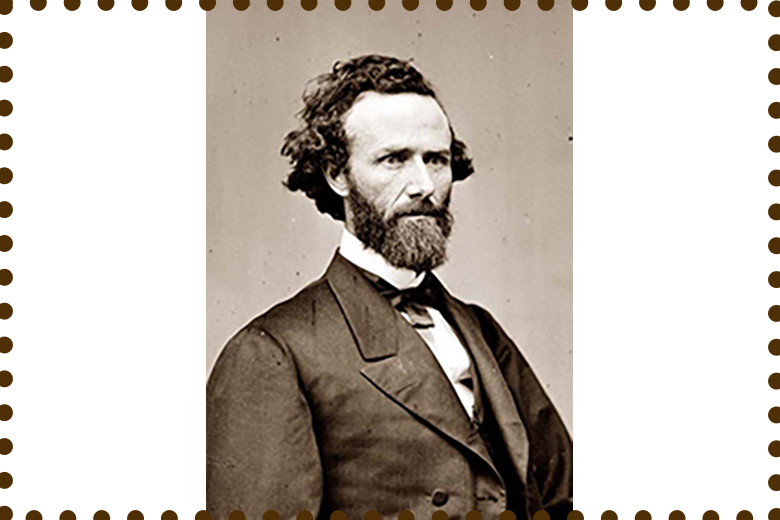

LOUISIANA, Mo. — Thirteenth Amendment author John Brooks Henderson might have gone along with changes being considered by voters in five states, and one that almost made it onto the ballot in Missouri.

After all, the Pike County lawyer broke six decades of constitutional rigidity with his plan to federally outlaw slavery.

At issue in modern efforts to change state constitutions that long ago adopted the amendment’s guidelines is the clause that allows “involuntary servitude” for people convicted of a crime.

Twenty states, including Missouri, still have such language on the books. Voters in Alabama, Louisiana, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont will decide Nov. 8 on removing it from theirs. A similar proposal in Missouri last spring did not get enough signatures to be put on the ballot.

Advocates backing an end to involuntary servitude at the state level hope it someday can be removed from the 13th Amendment.

Henderson’s original draft is closest to what would become the controversial law. The senator introduced it in January 1864 – six months shy of the 60th anniversary of the 12th Amendment’s passage in 1804. The last ratification of an amendment came in 1992, although it had first been discussed 202 years earlier.

“This proposition is to mark an epoch in the history of our country if it shall be adopted, and I take occasion now to express my sincere wish that it may become part of the Constitution,” Henderson announced in the Senate.

As with other slavery-ending proposals, it included the involuntary servitude exception. Henderson overwhelmingly focused on the need to stop humans from owning humans, and did not mention the exception in his remarks.

He also understood the reluctance to constitutional change, saying “this feeling of comity, this reverence of the letter and spirit of the organic law, this overwhelming desire to preserve the national unity, had, notwithstanding the existence of slavery, given us peace and prosperity, both public and private, unparalleled in the growth of nations.”

Henderson and other abolitionists knew the only hope the country had of reunification was an end to slavery, and the senator knew how to reach even the most jaded legislator.

“If slavery has committed this great iniquity once, what guarantee can it give of future forbearance and peace?” he asked. “It has none to give, and if it had a thousand guarantees, it would not give one.”

Involuntary servitude did not get much attention then because it had been used – and abused – in America long before the Constitution was adopted. So, it didn’t raise many eyebrows during an era that had seen the country torn apart by the Civil War – a nation which Henderson said would see additional conflict and death if slavery wasn’t addressed.

More exploitation of involuntary servitude over the next several decades finally led to legal battles. Laws forcing people to turn over wages in paying off debts were abolished, but those requiring convicted prisoners to work were upheld.

In 1916, the Supreme Court ruled the 13th Amendment did not ban “enforcement of those duties which individuals owe to the state.” Included were military service and jury duty.

Modern debate often focuses upon prison laborers, migrant workers, community service by inmates and sex trafficking suspects. Henderson could not have foreseen such issues, but he certainly believed the Constitution offered a durable guide rather than inflexible orders.

“Why was the power of amendment inserted at all?” he asked Senate colleagues. “It was to utilize the experience of the future, to correct error in the government.”

Even if more states decide to abolish involuntary servitude, the 13th Amendment is inviolate for now, and is likely to remain so. Its second section – which Henderson had no part in – gives Congress the “power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Agreement on such a major change would be improbable in today’s highly-divided political climate. Then again, there are supporters of ending the practice on both sides of the political spectrum.

And, even more importantly, the country is not in the midst of a bloody war, as it was when Henderson stepped up and changed history.

The authority to amend “was designed to let deliberate and mature convictions of public policy take a place in the organic law,” the senator said. “It was to be the safety valve of our institutions. Ours was to be a government of the people.”