LOUISIANA, Mo. — President Ulysses S. Grant hired and fired the Louisiana man who served as America’s first special prosecutor.

Now, a Grant expert will speak at one of the local places John Brooks Henderson called home.

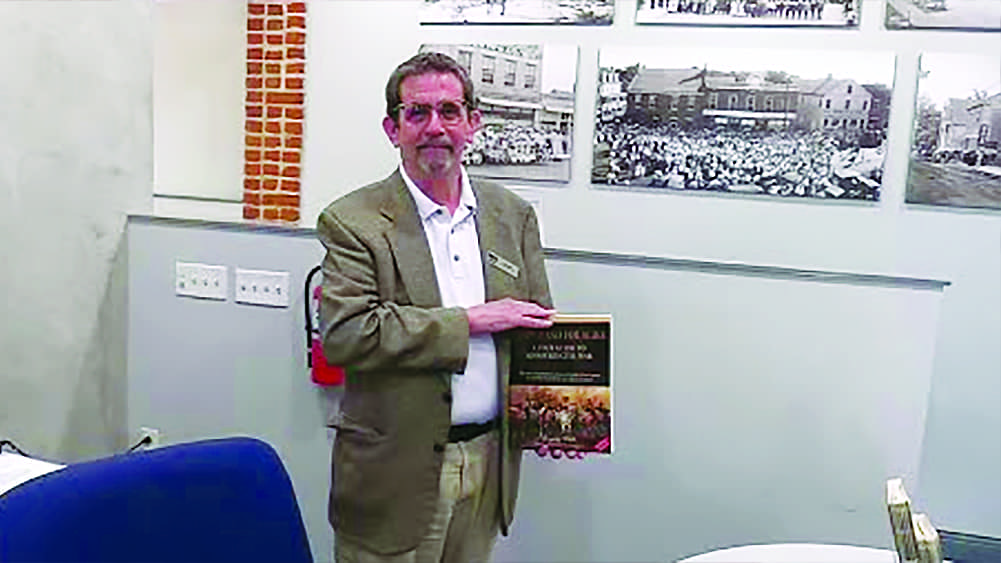

Greg Wolk of the Missouri Humanities Council will present “Forged in Missouri: Ulysses Grant & the Show-Me State.” The program is at 5 p.m. Sunday, July 17, at the Stephan and Pamela Moss house, 320 N. Main in Louisiana.

There is no admission charge, but seating is limited and people who plan to attend are asked to register by logging on to www.mohumanities.org/us-grant-bicentennial and clicking on “Register for speaker event.”

“Missouri was important to Grant, and now, two centuries after his birth, he is important to Missouri,” Wolk said.

Only three other states – Ohio, New York and Illinois – have strong links to Grant, Wolk noted. However, it was in Missouri where he began a career as an infantry commander during the Civil War, eventually being promoted to colonel and brigadier general.

Grant’s relationship with Henderson also is strong, albeit confrontational. He and his wife, Julia, “attended the high-society Washington wedding” of the Missouri U.S. Senator to Mary Newton Foote, Wolk said.

More importantly, Grant turned to Henderson when an impartial prosecutor was needed during the 1875 Whiskey Ring trials. He would be joined along the way by two other attorneys with Pike County roots, Republican David Patterson Dyer of Louisiana and Democrat James Overton Broadhead of Bowling Green.

The case involved powerful politicians, rich distillers, corrupt federal agents and dozens of greedy bit players in multiple cities who pocketed millions in alcohol tax revenues that should have gone to the government.

Grant disliked Henderson. The Missourian had been one of only seven Republicans who voted against the 1868 impeachment of Democrat President Andrew Johnson.

Henderson’s feelings about Grant apparently were mutual. In correspondence, one Missourian wrote to Grant that Henderson did not “like a bone in your body.”

Grant famously said “Let no guilty man escape” prosecution during the Whiskey Ring, but became enraged when Henderson’s investigation got close to one of the president’s closest aides. Henderson countered that Grant had been “grossly deceived and imposed upon by men who professed to be his friends.”

The prosecutor was fired without pay, with the dismissal announced in a telegram to Dyer. Grant eventually did something that no other sitting chief executive has done – testify as a defense witness in a criminal trial. Dyer and Broadhead continued for the prosecution.

Of 238 people indicted in the Whiskey Ring, 110 were convicted. Cases against the others were dismissed. The equivalent today of more than $70 million was returned to the federal treasury.

Henderson called the Whiskey Ring a “blot upon our government.” He hoped “the time is coming when a man who has the imperious force of character to resist the dictates of (political) party will be looked up to as a hero,” but resigned himself that “our nation may decay and fall before we learn this grand truth.”

In addition to Wolk’s July 17 presentation, a traveling exhibit for the bicentennial of Grant’s birth is planned for August at the Mark Twain Museum in Hannibal. Twain helped organize Grant’s memoirs and his company published them posthumously.