PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — Bill Whyte can’t wait to once again perform the song that started him on the way to a notable country music career.

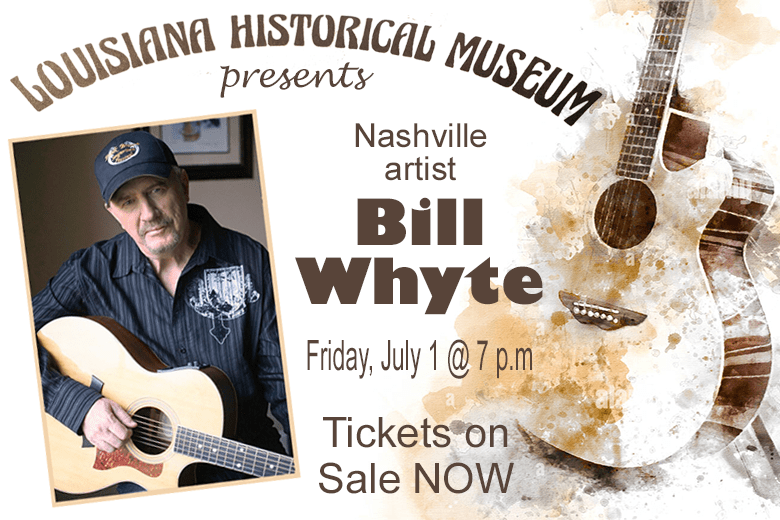

The Louisiana Area Historical Museum will host a concert by the Nashville recording artist at 7 p.m. Friday, July 1, at the Louisiana Elks Lodge, 120 N. Fifth. Tickets are $5 each for ages 13 and older and are available from museum board members or at the door. Those 12 and younger get in free.

Whyte has penned songs in just about every category from comedy to gospel. But his first recording – “Mo Mo the Missouri Monster,” about a Bigfoot-like behemoth that put an international spotlight on Louisiana in 1972 – is the one that, like the creature, lingers.

“I am so looking forward to this special event to sing about and talk about my old monster buddy,” Whyte said. “I’m hoping to have a couple of guests who will share what they know about Mo Mo and the creation of the song, too. Get your tickets!”

Whyte got his start at Bowling Green’s KPCR FM Radio, which is now KJFM. He remembers station owner Paul Salois and morning disc jockey Joe Lewis had written a poem about Mo Mo.

“I only tweaked what they wrote to make it fit the melody I wrote for the song,” Whyte said.

Johnny Nace was a popular country musician and deejay in Warrensburg, where Whyte went to college. Nace took the young musician to Nashville to record “Mo Mo.”

Whyte graduated from Central Missouri State University with a degree in mass media. A radio career included award-winning, high-profile stops in Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Milwaukee and Nashville. He also was a member of the United Talent roster owned by legends Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn.

Whyte has received multiple awards for songwriting. Among dozens of artists who have recorded his tunes are Ray Stevens, Joe Nichols, Cledus T. Judd, The Del McCoury Band, Linda Davis, Hillary Scott and Brady Seals.

While some songs deal with serious subjects, many tend toward the lighter side. Examples include “Things That Don’t Suck About Being a Guy,” “Honey Don’t Do List” and “Leave ‘Em Laughing,” One with which crowds can certainly identify is “The Dipstick Song (High Gas Prices at the Pump).”

The singer had great training for such lyrics. He wrote comedy for a syndicate in New York for almost three decades and once did stand-up in clubs. Whyte enjoys mixing genres during performances.

“Nobody feels bad when they’re laughing,” he explained. “And I love being able to provide that. But I also love performing a wide variety of songs that are the biggest part of my songwriting catalog.”

The best artists draw upon personal experience, and Whyte is no exception. Tunes that have the most impact usually offer nuggets of fact.

“The audience picks up on that,” Whyte said. “I do a song called “Face For Radio” because every bit of it was written about my long radio career, and every line is true. At the same time, funny songs make an impact because usually there’s some truth tucked into those songs, too. I write songs with our veterans and all of those songs are nothing but the truth from the eyes of a soldier. I’ll talk about that experience at the show.”

Whyte enjoys the intimacy of what he calls “listening audiences.”

“I played in a band for years and played to big audiences some, and that is a different kind of thrill,” he said. “But I love being able to sing my original songs and tell the stories behind those songs. And I love being able to talk ‘one-on-one’ with those in the audience about those songs and my life.”

That interaction is something vital to Whyte’s shows.

“It’s all about making a connection with the fans,” he said. “If I can do that, I’m going to enjoy the show more, and so are they. To look at faces that are laughing, sometimes crying, and responding to songs you’ve written is more rewarding than I can describe.”

The Louisiana gig will be a “very informal acoustic show,” Whyte promises. He plans to wear a Mo Mo shirt that the museum is selling, and says he’ll be “extremely disappointed” if fans don’t talk with him afterward.

“Hopefully, folks will feel like they are sitting in their living rooms listening to a friend tell stories and sing songs. I’ll do a mix of serious songs, gospel songs, songs that have been recorded by artists they will know, a patriotic song and certainly a healthy dose of funny songs. And, oh yeah, I’ll sing ‘Mo Mo,’ too.”

So, is Whyte a skeptic or adherent of the elusive beast?

“Oh, ya gotta believe in something, don’t ya?”

Mo Mo

Legend of Bigfoot-like creature refuses to die

Editor’s note: The following is updated from a story that originally appeared in Brent Engel’s 2019 book “They Call Us Pikers,” which is available from the author or at the Louisiana Area Historical Museum.

For every person who says it was a hoax, there’s at least one who believes.

It’s been 50 years since Louisiana was propelled into the world spotlight by stories of an elusive creature with a foul smell, a nasty disposition and an apparent appetite for small animals.

Forget that in the summer of 1972 a botched burglary would eventually lead to the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon, who overwhelmingly won re-election that year.

Put to the side that Arab terrorists were about to turn the good will of the Olympics into hatred as the games returned to Germany for the first time since Adolf Hitler had presided over them in 1936.

Don’t bother that it took only 36 cents a gallon to fill a gas-guzzling car, and that fuel shortages caused by an oil embargo would lead to long lines at the pumps within a year.

While our ears took in Jim Croce’s song about a bad dude from the South Side of Chicago named Leroy Brown, all eyes were on Louisiana.

The beast that became known as Mo Mo the Missouri Monster caused terror, intrigue, conjecture and more rumors than the number of rocks brought back from America’s final trip to the moon later that year.

It was generally reported as being six to eight feet tall and four hundred to six hundred pounds, with glowing red eyes, a rounded head and a horrible smell. It left behind three-toed footprints and emitted grunting or gurgling sounds.

There had been occasional reports of a “monster in the woods” in Pike County since at least the 1940s. But this time, things would be different.

“Something is going on in the area of Marzolf Hill,” the Louisiana Press-Journal said on July 18, 1972. “What it is no one seems to know for sure.”

The first sighting

What is believed to be the first sighting of Mo Mo had taken place a year earlier.

In July 1971, Joan Mills and Mary Ryan were driving along Highway 79 north of Louisiana on their way back to St. Louis when they decided to have a picnic at a scenic stop.

“We were eating lunch when we both wrinkled up our noses at the same time,” Ryan later recalled. “I never smelled anything as bad in my life.”

At first, the women thought the stench could be attributed to a family of skunks, but they then saw a “half-ape, half-man” emerging from a thicket.

“The weeds were pretty high and I just saw the top part of this creature. It was staring down at us,”

Mills said. Ryan said the monster had hair over its body like an ape, but its face was “definitely human.” Mills claimed it made a “gurgling” sound like someone trying to whistle underwater.”

The women fled for their car and locked the doors as the creature stepped toward them. It reportedly caressed the hood of the Volkswagen before trying to open the doors. That’s when Mills realized she had left her purse with the car keys on the picnic table.

“It walked upright on two feet and its arms dangled way down,” Ryan recalled. “The arms were partially covered with hair, but the hands and the palms were hairless. We had plenty of time to see this.”

The women honked the horn, which initially startled the beast, but it soon got used to the noise. It finally gulped a peanut butter sandwich and stomped back into the woods.

Mills jumped out long enough to get her purse and the women were on their way again. A report was submitted to the Missouri Highway Patrol, Mills admitted the story was a bit unbelievable, then added a caveat that would lead to even more suspense.

“We’d have difficulty proving that the experience occurred, but all you have to do is go into those hills to realize that an army of those things could live there undetected,” she said.

The sighting that would put the focus on Louisiana came after three siblings saw a large, hairy creature at 3:30 p.m. Tuesday, July 11, 1972.

Interrupted routine

It was just another hot summer day at the Harrison home at 1004 Allen Street near Marzolf Hill — until the screams.

Fifteen-year-old Doris Harrison had been cleaning a bathroom sink when she heard the cries, which came from her brothers, eight-year-old Terry and five-year-old Wally. The boys were playing outside.

Doris looked out the window and could hardly believe the sight. A hair-covered creature stood at the edge of the woods with a dead dog under one arm and specks of blood on its fur. Doris noted a pungent smell that wafted through the open window.

“It scared me so bad,” she later said. “It scared me to death. I was afraid it was going to come and get us.”

Unable to determine what the creature was, Doris was certain of one thing — it wasn’t a man and it wasn’t any animal she’d ever seen.

Doris told her brothers to come inside and called her father at work. Edgar Harrison was about as solid a citizen as could be found. The 40-year-old had been in the Army during the Korean War, had worked for the Louisiana Board of Public Works since 1952 and knew every nook and cranny of Marzolf Hill, which is now called Star Hill.

He was a deacon in the Pentecostal church and he and his wife, Betty, owned a restaurant on South Main. If Harrison held any doubts, he apparently never expressed them. He told authorities his children had seen an unidentifiable “black object about seven feet tall.”

It was soon hard to tell which outnumbered the other — speculation or reported sightings. Speculation ran the gamut from Bigfoot to a hog that had escaped from a vehicle accident in May. Sightings were reported by people of all ages at all times of the day and night.

A neighbor of the Harrisons heard loud screams and animal growling. A farmer said he encountered the creature not far from his house. Pets were kept inside to keep from them from becoming supper for sasquatch.

“We heard it a few days later,” Doris Harrison recalled. “It was a roar. I’ve heard bobcats and other animals, and it was nothing like that. My dad just started hollering ‘Y’all better go! It’s coming!’”

“I hope this thing quiets down and we don’t get a whole lot of adventure-seekers here from all over the country,” Gus Artus, a wildlife official with the Missouri Department of Conservation, told the Louisiana Press-Journal.

Of course, there was no way to keep a lid on things. A frenzy was ignited when newspapers around the nation picked up the story. Men armed with shotguns searched to no avail.

Fearing that someone would end up shooting the wrong bipedal, Police Chief Shelby Ward on July 18 declared Marzolf Hill off limits.

On July 14, a prayer meeting was held at the Harrison home. As it ended, Edgar Harrison and others described seeing two “fireballs” shooting through the sky over Marzolf Hill. The first was white and the second green. The lights may have been flares designed to spook the creature into revealing itself, but no one claimed responsibility for firing them.

“Whatever it is, it runs from people,” Artus said. “My advice is that people in that neighborhood should go inside their homes. If they are frightened, they should lock their doors. If something comes around their houses, they have plenty of time to call the police or a neighbor. They can defend themselves from inside their houses if necessary. They should ask the outsiders to go home.”

On July 19, Artus led a three-hour search of 100 acres that included law enforcement and volunteers. Two dog graves had been disturbed and the bones tossed about. There were no run-ins with Bigfoot, but a man named Robert Pappenfort told the searchers to get off his land.

“I am convinced, and the rest of us are also, that there is nothing that even looks like a ‘monster’ on Marzolf Hill,” Artus said afterward.

Naturally, that didn’t stop purported sightings. A woman claimed a “long-haired thing” crossed the highway near her home. In an era when many younger men were avoiding regular haircuts, one father couldn’t resist a stab at humor.

“From the description, it sounds like the guy who’s going with my daughter,” the pundit quipped.

The fun didn’t stop there. Area radio stations dedicated the 1965 song “Wooly Bully” by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs to Mo Mo.

“Will the story die?” the Press-Journal asked. “Or, will it continue to expand, the stories growing larger and wilder until everyone in Louisiana feels ridiculous?”

Uh, get ready for the absurd.

The world watches

It didn’t take long for folks with fancy titles to descend upon Louisiana.

Everyone from cryptozoologists to unidentified flying object researchers wanted a piece of the action. If every stone had been uncovered, they were about to be flipped again.

National television networks sent crews. Reporters for The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal were among journalists who came to town. It was the kind of widespread attention Louisiana hadn’t experienced since the opening of the Champ Clark Bridge more than 40 years earlier.

Things really got weird when Hayden C. Hewes of the International Unidentified Flying Object Bureau of Oklahoma City showed up. He camped in the Harrison’s backyard, toured Marzolf Hill and interviewed alleged witnesses.

Like all the rest, he didn’t find anything, but offered a bizarre theory that the creature had been left behind by UFOs or was an “unknown form of hominid” similar to a Neanderthal.

“Mo Mo must be taken alive,” Hewes implored. “He’s the greatest anthropological find in history.”

On the night of July 20, Harrison accompanied Richard Crowe of the Irish Times to Marzolf Hill. Among their findings were large footprints and a shack where Crowe said they “smelled an overwhelming stench that could only be described as resembling rotten flesh or foul, stagnant water.”

Harrison claimed the creature was nearby, and though they smelled the awful odor twice more that night, the search did not turn up a Bigfoot.

Clyde Penrod of Louisiana made a plaster cast of a three-toed footprint that Mo Mo may have made. No identified mammal walks on three toes. The cast is the only remaining physical evidence. Penrod’s daughter, Christina Windmiller is among the skeptics.

“Whatever it was, it was big,” said Windmiller, who was just a year old when the sightings took place. “It was really nice to think that it was real, but it probably wasn’t.”

On July 25, 1972, the creature was still frontpage news in the Press-Journal, but the top story was groundbreaking for construction of Pike-Lincoln Technical School in Eolia. The first use of the term “Mo Mo” appears to have been in media reports two days later. Residents were divided on the creature’s existence.

“I want to believe that it’s there,” Beverly Wacker told the Press-Journal. “Too many people have seen it for me to think it’s not real. I just don’t believe that all the many people who have seen it would be making it up.”

“I don’t think there is such a thing for this reason: If a small or large animal escaped from a zoo, we’d catch him before he got a half-block away,” said E.A. Humphrey. “In other words, if there were such a monster, we’d catch him.”

Ten-year-old Tom Jaeger of Clarksville said that he thought Mo Mo was “nothing but a big fake.” His seven-year-old brother, Asa, added “If I saw the monster and I had a gun, I’d go pow-pow-pow.”

One 14-year-old dressed in a horse hair jacket and blond wig, then danced around the parking lot of a gas station on Georgia Street, saying his object was to “scare some girls.” A women’s bowling team printed Mo Mo shirts and called themselves the “Zephyr Monsters.”

Despite the frivolity, Harrison remained adamant. “There’s something up there,” he said. “We just haven’t found it yet.”

There was another serious aspect of the Mo Mo saga, and it was a good one. Louisiana businesses were seeing a big increase in the bottom line, thanks to all of the people who were coming to town.

Merchants capitalized on the trend by hosting what they called a “Mo Mo Sidewalk Sale” on Aug. 4 and 5, 1972. The promotion included bargains such as denim jeans for $2.50 at JC Penney. The Carol Ann Shop had $60 coats for just $20. The IGA Foodliner at the west edge of town offered sweet corn for 89 cents a dozen. A restaurant made what it called a “Mo Mo Burger.”

As expected, the streets were packed with shoppers. The event turned out so well that “Mo Mo Days” were held for years to come.

Not so fast

It’s hard to fool Priscilla Giltner.

As an educator at Louisiana High School, she had seen just about every trick in the book. So, when it came to Mo Mo, there was just cause for disbelief.

Giltner says Mo Mo was nothing more than a prank pulled off by several students. She has consistently declined to identify them, despite repeated requests by reporters and others.

“I had them in school and one of them dressed up like Mo Mo,” she told The Herald-Whig in 2012. “They were up on Star Hill for whatever reason, and for whatever reason, God only knows, they decided to pull this trick. I really don’t think they counted on anybody actually seeing them up there.”

Giltner theorizes the boys didn’t realize their antics would have consequences that were never intended. Still, observers noted that, good or bad, Mo Mo shined an international light on Louisiana.

“It kind of sparked this town up,” Giltner told The Herald-Whig. “It’s kind of our thing. We don’t have much, be we do have Mo Mo and nobody else can claim Mo Mo but us.”

The initial scare didn’t last long. While the Press-Journal continued its coverage in 1972, it also asked readers to turn their attention to the primary election scheduled for Aug. 8, saying “let’s put down our guns, take down our barricades and go out and vote.”

Other reports in following years claimed Mo Mo made appearances along the Mississippi River. Skeptics continued to cast misgivings. The first question was the one all doubters ask: Why is there no concrete physical evidence? Despite all of the videos, photos and accounts, such a creature has never been caught and bodies or bones have never been found.

As with other Bigfoot-like monsters, Mo Mo spawned books, television shows, music and movies for years. Bill Whyte, Joe Lewis and Paul Salois of KPCR Radio in Bowling Green teamed for the song “Mo Mo the Missouri Monster.” The tune, which can still be heard locally on KJFM Radio, gained Whyte his first trip to Nashville and a recording career.

“It’s the little song that just keeps keeping on,” Whyte said in 2012. “Through the years, I get e-mails from time to time asking about the song and the story. I’m amazed at how long it’s lasted. And it all started with a few lines on a paper from Joe Lewis and Paul Salois.”

In 2019, the Ohio-based documentary company Small Town Monsters filmed “Mo Mo: The Missouri Monster” in Pike County, and other productions have been done.

Edgar Harrison died at age 76 on July 25, 2008. Doris Harrison married Richard Bliss on July 8, 1973. He died at 61 on Jan. 9, 2014 and she passed in 2021. Hayden C. Hughes continued to write and lecture about the paranormal. He died at 73 on Sept. 13, 2017.

Despite being teased and hounded for years after the 1972 sighting, Doris Harrison Bliss never strayed from what she saw.

“To me, it was a monster,” she told the Destination America television show “Monsters & Mysteries in America” in 2015. “Before I saw the creature, everything was fine. Seeing this creature changed my life.”

The Louisiana native had a message for those who did not believe her, then or since.

“I used to hate talking about it, because people made fun of me and stuff, but now — and you can pardon my French — they can kiss my ass,” she told The Herald-Whig. “I saw what I saw and I heard what I heard.”

One last thing

In August 1972, a switchboard operator at a Kansas City area newspaper sent a letter to Louisiana officials.

Mary Jo Pressler said she and her friends had followed the Mo Mo story with great interest and hoped coverage would continue.

“The thing that seems strange to me is what has become of Monster Mo Mo?” Pressler wrote. “We no longer hear of him and perhaps he was a figment of our imagination, or should I say, the people of Louisiana? But whatever it was, it was fun and exciting.”