BOWLING GREEN, Mo. — A Pike County man who played for the Cleveland Indians and later broadcast games for the team is being recognized by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Jack Graney of Bowling Green is the 2022 recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award, which the Hall of Fame presents each year to an outstanding broadcaster. He will be recognized posthumously during ceremonies in July at Cooperstown, N.Y.

Graney played for the club that won Cleveland’s first championship in 1920 and was at the microphone for the Tribe’s last series victory in 1948.

“I always tried to give the fans an honest account,” Graney told broadcast journalist and baseball historian Ted Patterson. “It was a tremendous responsibility and at all times I kept in mind the fact that I was the eyes of the radio audience. I was like an artist trying to paint a picture. I never tried to predict or second-guess, even though I had played the game. I just tried to do my best, and I hope my best was good enough.”

Leading off

John Gladstone Graney was born on June 10, 1886, in St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada.

Scouts noticed his pitching ability at age 11, and he played professionally for the first time at age 19 with his hometown St. Thomas Saints.

Graney spent two seasons in the minors before being drafted in 1907 by the American League’s Cleveland Naps, who were renamed the Indians in 1915.

On April 30, 1908, Graney made his Major League debut with Cleveland. The lefty had a killer fastball but little control. He pitched in two games, giving up six hits and two runs in just three and one-third innings to finish with a whopping earned run average of 5.40.

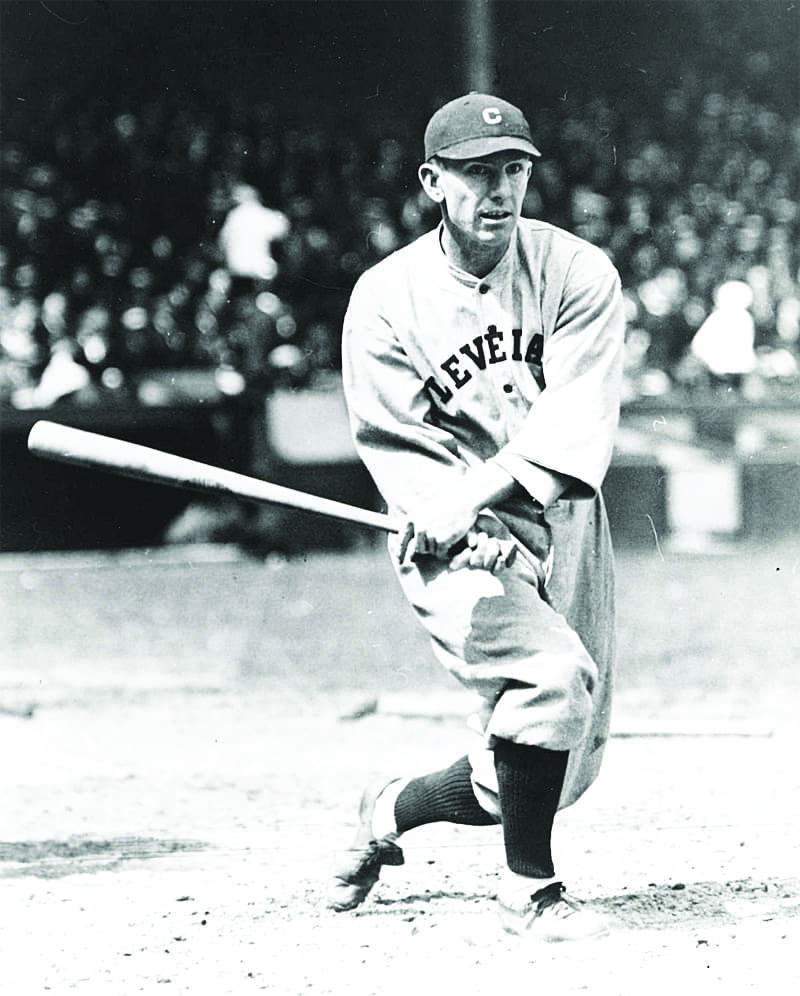

A broken finger from an opponent’s line drive kept Graney on the bench for a month. He was sent to the minors and had been converted to a left fielder by the time he came up to stay in 1910. The five-foot-nine-inch, 180-pound sparkplug would spend the next 12 seasons frustrating pitchers and throwing out hitters who tried to turn singles into extra bases.

Graney was nicknamed “Three-and-Two-Jack” because he rarely swung until deep in the pitch count. As Cleveland’s leadoff hitter, it was his job to get on base any way possible. Working the count eventually wore down all but the strongest hurlers.

“Not only does waiting a pitcher out impair his confidence and his control, but it also makes him work harder,” Graney once said. “A safe hit may be made on the first ball pitched. A pass is much more wearing on the pitcher’s arm.”

Graney’s highest batting average was .299 in 1921, but in 14 seasons he twice led the American League in walks and reached base a little over every three at bats.

As a lefty, Graney had a slight edge at what was otherwise a hitter’s rectangular nightmare known as Cleveland’s League Park.

The right field wall was only 290 feet from the plate, although home runs had to clear an additional 40-foot fence. Left field had a five-foot fence but was 375 feet away – enough to accommodate a football field. Center was a whopping 460 feet away, and at one point just a little bit toward left it extended to 505 feet. For comparison, Busch Stadium in St. Louis has dimensions of 336 feet in left, 400 feet in center and 335 feet in right.

“Opposing pitchers will tell you that Jack Graney is one of the hardest men in the league to pitch to,” wrote the Washington Evening Star.

During a 5-5 tie in the top of the 15th inning against the Red Sox in Boston on June 11, 1913, Graney stole home off of Dutch Leonard not long after teammate Ivy Olson did the same – a record that still stands.

Speed and a strong arm made Graney an excellent outfielder. He finished with a career .953 fielding percentage.

The funky shape of League Park meant that even the home-towners had to be on their toes. Line drives off the steel beams that held up the right field fence sometimes would end up ricocheting toward left field. One of Graney’s tutors was teammate and future Hall of Famer Tris Speaker, considered one of the best centerfielders ever and a player whose glove was known as “the place where triples go to die.”

Speaker said that if Graney’s eyes hadn’t been ruined by the blinding sun in left field, he could have been an incredible hitter.

Great personality

Graney was a fan favorite in Cleveland, and it wasn’t always his bat or glove that gained him fame.

Starting with the 1913 season, Graney was in charge of the Naps’ bull terrier mascot, Larry. The dog would do tricks, chase fans with straw hats and retrieve balls in batting practice. He hit the road with the team and was even introduced to President Woodrow Wilson. When the mutt needed a respite, it would be sent by steamer and streetcar to Graney’s parents in Canada.

The normally adept mascot had to be put down in July 1917 after getting distemper when becoming lost inside a Cleveland building for two days.

Like just about every player, Graney didn’t always agree with umpires. However, he didn’t get angry. The Chicago Day Book related a story from umpire Jack Eagan about a Graney at-bat in 1911. The pitcher delivered a fast, high throw.

“Did you have the nerve to call that a strike?” Graney asked.

“Correct,” Eagan replied.

“Where was the ball?” Graney implored.

“Right across your letters,” the umpire said.

“You mean right across the letter on my cap,” Graney said as he swung at the next pitch.

Umpire Silk O’Loughlin claimed in 1917 that he had never made a mistake, but “I will admit that when Jack Graney makes a protest on a called strike, I wonder if I really did miss one. He sure is a hawk when it comes to standing up to the plate and letting the bad ones go by.”

Of course, no one is at the top of their game every day.

On April 23, 1918, the only two runs scored by the St. Louis Browns in a Cleveland victory came when Graney didn’t chase a line drive because he thought it was foul. The umpire ruled it fair, and Joe Gedeon drove in himself and another runner with an inside-the-park home run.

The lighter moments helped endear Graney to fans.

In a 1916 game, Graney was the last batter standing between the Philadelphia Athletics’ Joe Bush and a no-hitter. Graney yelled out to Bush and asked how much he’d be willing to pay if Graney took a dive.

“You know this means a lot to you, Joe,” Graney taunted. “What do you say?”

Bush promptly got Graney to fly out and end the game. The Cleveland player was the first to congratulate Bush.

In another 1918 game, Graney was sent in to bat for a pitcher. The stadium announcer did not speak the substitute’s name clearly.

“Who is he batting for?” yelled a fan.

“Not batting for, but by request,” Graney answered with a smile.

“Unless you show something, Jack, all further requests will be withdrawn,” the fan blurted.

Graney promptly proceeded to spank one over the right field wall, one of only 18 career home runs. In a 1919 exhibition game, Graney rode out to left field on a horse. It wasn’t all fun and games, however.

In 1920, Graney’s best friend and travel roommate, Southern Illinois native Ray Chapman, died after being hit in the head on a pitch from the New York Yankees’ Carl Mays at the Polo Grounds. Chapman remains the only Major League Baseball player to die as a result of an injury on the field. More than 40 years later, Graney still seethed.

“People ask me today if I still feel Mays threw at Chappie,” Graney told interviewer Regis McAuley in 1962. “My answer has always been the same – ‘Yes, definitely.’”

The beaning took place the same year the Indians won their first World Series. Graney played in three Series games, but didn’t get a hit. He finished his career two years later with nine hits in 37 games and ended the season managing the Indians’ farm team in Des Moines. His overall numbers were 706 hits in 4,705 at-bats for a lifetime batting average of .250. He played in 1,402 games, scored 1,178 runs, had 420 runs batted in and was on base a total of 1,609 times.

Graney didn’t know it, but there was still a lot of baseball left.

Second calling

Retiring from the game in Graney’s day meant finding another job pretty quickly.

Extravagant salaries were decades away. From 1923 to 1927, Graney ran a very successful Ford dealership in Cleveland. He later was involved with investments, but the Great Depression emptied his pockets.

In 1932, the Indians switched the team’s broadcast contract to WHK Radio. When none of those who auditioned proved right, Indians General Manager Billy Evans called upon Graney. The one-time player had never been behind a microphone.

“Before my first broadcast, I was so nervous I almost changed my mind and ran out of the booth,” he later recalled.

Graney had a high-pitched voice, but a smooth and authoritative delivery backed by vast knowledge and an enthusiastic spirit.

Like a lot of Depression-era teams, the Indians did not send announcers on road trips. So, Graney and his partners relied upon telegraph reports when broadcasting away games. Graney could sit in a studio and do recreations of games hundreds of miles away like no one else.

“His voice dripped with sincerity and crackled with vitality,” remembered Bob Dolgan of the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper. “He wasn’t bored with baseball; you could tell he loved his job. He made baseball sound like sport.”

Once again, the fact that Graney had played in every American League park gave him an advantage over other announcers.

Graney broadcast All-Star Games, World Series, Bob Feller’s first no-hitter and thousands of other contests before leaving radio and television in 1953. The only year he stayed out of the booth came not long after his son, Jack Jr., was killed in a 1943 military training accident at Fort Bragg, N.C. Graney also broadcast Cleveland Barons hockey before putting way his microphone.

“He was a careful reporter and observer,” Dolgan wrote.

The late St. Louis Cardinals announcer and Ford Frick Award winner Jack Buck remembered listing to Graney.

“I didn’t want to be a policeman or fireman,” Buck recalled. “Jack made me want a living calling ball.”

Mr. Firsts

Graney could count many illustrious firsts in his dual careers.

On July 11, 1914, he was the first batter a young Boston pitcher named George Herman Ruth faced in the rookie’s Fenway Park debut, a game The Babe won 4-3 before becoming better known for his hitting.

On June 26, 1916, Graney was the first player to wear a number on his uniform in leading off against the White Sox in a 2-0 home victory. The numbers were pinned to players’ sleeves, and corresponded with those printed on scorecards. Graney was also the first former player to become a broadcaster.

He and his wife, Pauline, moved to Bowling Green to be closer to their daughter, Margot Graney Mudd, who co-founded with her husband, J.O., the business known today as Bibb-Veach Funeral Home.

“They lived a pleasant existence there, the tranquility interrupted only by frequent phone calls from Cleveland sportswriters wanting to do interviews with the great Graney,” Dolgan wrote.

Graney’s final years were spent in a quiet, unassuming house along South Court Street near Bowling Green City Park, where he often helped kids learn to appreciate the game he loved. He died at age 91 of natural causes on April 20, 1978, at a nursing home in Louisiana, where he had been for three months. Pauline followed five years later. They were married for more than 60 years and are buried in Bowling Green Memorial Gardens Cemetery.

In 1984, Graney was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. Three years later, the Hall began bestowing the Jack Graney Award to media members for contributions to baseball in Canada.

In 2012, Graney was elected to the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame as a broadcaster, and a tribute to him can be found in the press box at Progressive Field.

However, the ultimate tribute is now about to happen – induction at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Hall President Josh Rawitch called Graney “one of the National Pastime’s radio legends” for his “attention to detail and love for the game.”

“Jack Graney was a pioneer in the broadcast industry, not only establishing a model for game descriptions in the earliest days of radio, but also for blazing a trail for former players to transition to the broadcast booth,” Hall of Fame President Josh Rawitch said in a news release.

Editor’s note: The following is adapted from a previously-published piece by award-winning Pike County author, journalist and public relations professional Brent Engel of Louisiana.