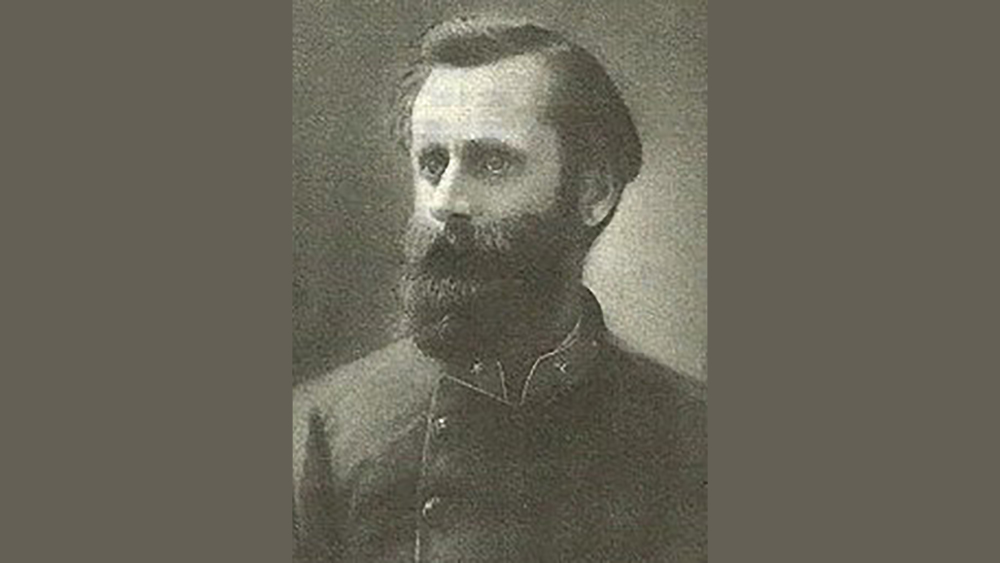

PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — Placid man is a terror on the battlefield. He was a smart, successful and staid Pike County businessman.

But when the Civil War broke out, John Quincy “Jack” Burbridge became known for a deadly directive offered to Confederate comrades.

One rebel commander called Burbridge a “thorough soldier” who was “always ready for a fight.” A Confederate veteran remembered him for making “a notable appearance” on every battlefield.

Of course, Union supporters had a much different view. Louisiana grocery owner Edwin Draper accused Burbridge of being among those who were “combining to encourage new risings and raids of rebels.”

The man one soldier called “graceful” despite being of “less than medium height” was born in Pike County on May 21, 1830. A grandfather, Rowland, was a Revolutionary War veteran. His father, Benjamin, was a Kentucky native and Pike County pioneer who in 1835 built the first steam mill in Louisiana.

A devout Catholic, Burbridge attended St. Louis University. As with many other Pikers, he was part of the California Gold Rush starting in 1849.

Upon returning to Missouri in 1852, he became a banker and landowner with properties that today would be valued at more than $550,000. On Jan. 13, 1856, he married Missouri-born Sarah Ann “Sallie” Swink, who was nine years younger. The couple would have two children before her death at age 28.

Fierceness was not always part of Burbridge’s demeanor. Even before hostilities broke out in April 1861, he was part of an effort to avoid conflict.

Supporters and opponents of slavery met at Louisiana Concert Hall on Dec. 22, 1860, to see if conciliation could be found. It could not, and the meeting descended into bickering. Burbridge served as secretary, and had a hand in drafting resolutions that were decidedly pro-Southern.

Meeting leaders left open a door for what they called “patriotic men” in the North to “make a common cause with us in destroying and driving from power and influence before it is too late” newly-elected President Abraham Lincoln and others who favored abolishing slavery.

Much like political parties today, a majority of those who attended sought to gain without giving. While saying they stood by the Union and the Constitution – a document they called the “anchor of our liberties” – there was no mention of freeing indentured African Americans, only a call for concessions and a redress of perceived wrongs.

The resolutions were endorsed at another meeting in Bowling Green on Jan. 28, 1861. After the Confederates fired upon Fort Sumter, Burbridge organized a unit of the Missouri State Guard, which was loyal to the South.

Recruitment was one of the commander’s strongest abilities, and he brought hundreds of men to the rebel cause. Those that didn’t bring weapons from home often were given guns Burbridge had pilfered from Union outposts.

Millwood resident Joseph Aloysius Mudd, who in 1909 would publish an illuminating book about Confederate activity entitled “With Porter in North Missouri,” recalled seeing Burbridge drilling troops near his Lincoln County hometown. Mudd was so impressed that he “immediately enlisted.”

Burbridge “succeeded in the dangerous business of leading southern recruits out of Union-occupied Missouri,” wrote Bruce Nichols in volume four of “Guerilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri.”

A promotion to colonel came on July 3 and two days later he led his men in battle at Carthage, leading one Confederate officer to applaud his courage and spunk.

Both sides were amazed when Burbridge survived a shot to the head at The Battle of Wilson’s Creek on Aug. 10. By the fall, he had recovered and was placed in command of a cavalry outfit.

On Jan. 16, 1862, the colonel helped organize the First Missouri Infantry Regiment. Ephraim McDowell Anderson, a Tennessee-born resident of Monroe County, wrote in his memoirs that the unit’s “courage never faltered in the darkest hour of trial” and its “valor was consecrated by a devotion unsurpassed in all the annals of our war.”

Burbridge saw action in several states, but was usually taciturn. In letters to superiors that have survived, a banker’s reserve emerges from his adherence to facts and a resistance to speculation.

Confederate Gen. Earl Van Dorn noted his “distinguished conduct” at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. The Little Rock True Democrat called him a “man for the times.”

Even greater praise came from two revered rebel generals. John Bullock Clark was a Harvard law graduate who would later serve as a Missouri Congressman. Thomas Alexander Harris had been fighting battles since age 12, including time spent in the Union army before the war.

The generals cited Burbridge’s “conspicuous gallantry” and said he was “a gentleman of strict sobriety, fine judgment and inexhaustible energy.”

The colonel was captured in Arkansas on Aug. 24, 1863. He would spend time in Yankee prisons at Memphis, St. Louis and Baltimore before being paroled from a lockup in Virginia on St. Patrick’s Day 1864.

Upon returning to Missouri, Burbridge led a guerilla campaign against Union forces – “dutifully serving the Confederacy where he was sent,” according to Confederate Col. Jeff “The Swamp Fox” Thompson, who got his nickname for being adept at avoiding Union capture. “That was his reputation.”

The commander also gained notoriety for a particularly sinister edict that seemed uncharacteristic of his nature. It distinguished him from other officers and proved a hit among his troops.

“Burbridge endeared himself to the men by admonishing them to aim at the enemy’s breech’s button,” wrote Confederate infantry Captain Eathan Allen Pinnell. “A wound in that region, he explained, nearly always gives the victim time to prepare to meet his Maker.”

A recommended promotion to brigadier general never came. Burbridge survived the war and afterward moved to St. Louis. He later became a railroad executive and served as mayor of Jacksonville, Fla.

Burbridge’s younger brother, Clinton, also was a Confederate officer and Draper told Union authorities that both of their wives were rebel spies.

Jack Burbridge died at 62 on Nov. 14, 1892, and is buried in St. Louis.