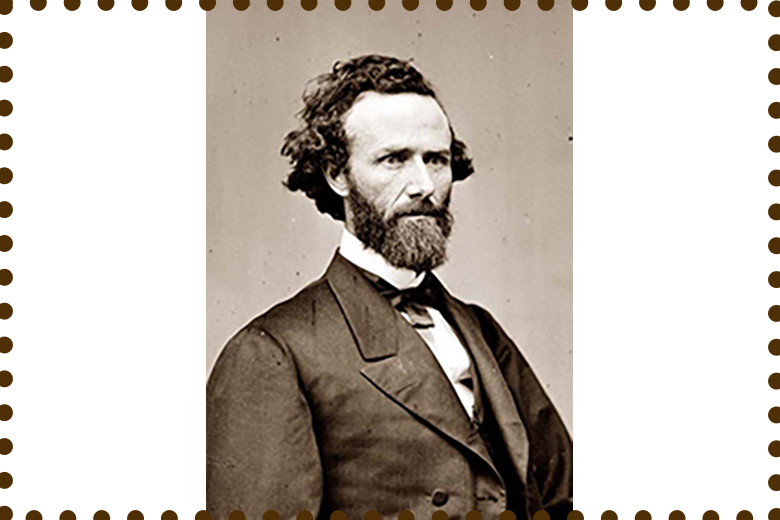

PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — There’s no way of knowing what Pike County lawmaker John Brooks Henderson would have thought of modern attempts to change a key part of the constitutional amendment he drafted.

He only addressed the topic briefly before his death in 1913. But if first-hand experience is any indication, Henderson might have agreed that a change was needed.

The new effort proposes removing from the 13th Amendment wording that allows indentured servitude as punishment for those convicted of a crime. The provision which bans slavery would remain.

The focus at the time Henderson introduced the amendment in 1864 was to free four million people held in human bondage, prevent its spread to new states and end the Civil War.

Indentured servitude was controversial from its introduction by the first colonists to Virginia in the early 1600s. However, there were two huge differences between servitude and slavery. People chose to become indentured and were protected by the law. Not so with slavery.

An estimated 300,000 people bartered themselves during the 1600s, despite its harshness and potential for abuse. The practice continued at a reduced pace over the next two centuries.

Henderson knew plenty about indentured servitude and slavery. He was born in Virginia and came to Missouri with his family at age six. As a boy, Henderson saw slaves being sold at public auctions.

By the time he was 10, Henderson’s parents had died, leaving his care and that of three siblings to neighbors. Children had few legal rights at the time. Henderson faced being “bound out” to Troy cabinet maker Oliver Simonds until he was 18.

“John was a red-headed, quick-tempered fellow, and from the beginning took a dislike to Simonds,” recalled Henderson friend David Patterson Dyer. “After working for a month or so, he and Simonds got into a fight in which the boy got the best of it.”

Authorities moved Henderson to the Billy Browning farm, where he excelled.

“This was the beginning of a career hardly surpassed anywhere in the history of the United States,” Dyer said. “If ever there was a self-made man in this country, John Brooks Henderson was that man.”

St. Louis historian Kirby Ross wrote that Henderson “overcame his circumstances” with involuntary servitude to become an educator, lawyer, military leader and leading legislator at a critical point in American history.

With outbreak of the war in 1861, Henderson was what top Confederate commander Thomas L. Snead called “the most conspicuous opponent” of Missouri seceding. Appointed to the U.S. Senate in 1862, the Louisiana attorney met regularly with President Abraham Lincoln to strategize about ending slavery and reuniting the country.

Henderson said a lot about human bondage but nothing about indentured servitude in the drive to pass the 13th Amendment. His silence likely was acknowledgement that compromise would be needed to get the measure approved, despite his own skeptical view of servitude.

The senator saw the amendment as being strictly about freedom. As with Lincoln, he believed the country could not be reunified with slavery intact.

“If the moral conflict proved to be unceasing before the war, it will be truly irresistible hereafter if slavery remains,” he said.

In writing the amendment, Henderson used as a guide the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, a forbearer of the Constitution that included a ban on slavery and allowed servitude only for convicted criminals.

Henderson left out “whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” in his first version. The words later were inserted by others.

“If it added nothing of substance to my original draft, it detracted nothing, and possibly made it less liable to misinterpretation,” Henderson said.

The indentured servitude provision would later be corrupted by opponents of the 13th Amendment and the two that followed. Examples of people being subjugated, especially blacks, would become numerous as segregationist politicians used oppressive or spiteful laws to require some sort of obligatory bondage as punishment.

Henderson did have a few words on the topic. They came in the April 1909 edition of National Magazine.

While expressing surprise that the ‘punishment for crime’ clause could be “impose by any authority other than the duly constituted tribunals of justice,” the senator offered words that perhaps can serve as a guide during today’s consideration of 13th Amendment changes.

“While clearness of expression is desirable in the framing of laws, brevity is equally desirable, provided the language used clearly conveys the purpose sought,” he wrote.