PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — Pike County residents targeted in 1864 rampage.

The Kill List, Part 1

What would you do if your name was on The Kill List?

Pike County clearly encapsulated the contempt between North and South during the Civil War. One of the most heinous illustrations was an inventory of 52 residents targeted for death in 1864 because they purportedly had Confederate sympathies.

A register of names frustratingly remains uncertain because the list apparently has been lost, but one account claims seven or eight men indeed were murdered. Two who avoided being victims made sure the story was told.

Allegiances divided many Pike County residents during the war, even within families, and the ironies could not have been more profound:

*The area was settled largely by people with Southern roots, but it was Virginia-born men such as Bowling Green lawyer and slavery supporter James Overton Broadhead who helped keep Missouri from seceding.

*At the start of the war, at least one in five Pike County residents was owned by somebody, yet Louisiana legislator and one-time slave owner John Brooks Henderson would draft and introduce a constitutional amendment outlawing indentured servitude.

*Some strict constitutionalists fanned the flames by allowing or supporting what were arguably illegal or, at the very least, questionable actions.

The 1883 book “The History of Pike County, Missouri” offers many Civil War references. One says that the county as well as the state had “passed through stormy times, but the clouds of passion and the feeling of hate, once so threatening, have entirely disappeared.”

If only that had been the case 20 years earlier.

Slippery slope

The Kill List had its beginnings long before any names were written down.

Four months after Fort Sumter was fired upon, martial law was declared in Missouri, allowing Union forces to exercise command over civilian authorities.

The order was not meant to foster abuses, but in practice gave the green light to a multitude of harassments and injustices against anyone accused of empathizing with the South.

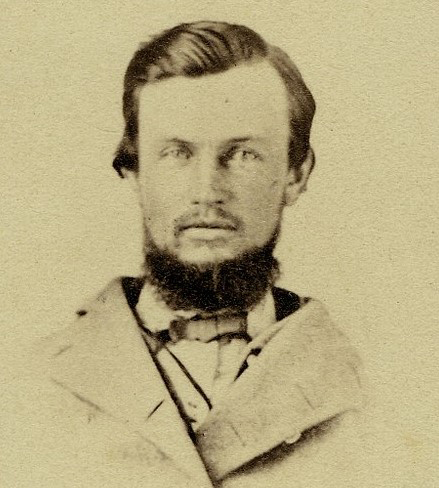

One of those hounded was Louisiana Weekly Union newspaper editor James Monaghan, a Pennsylvania-born champion of the Northern cause who nonetheless supported slavery. He was an ideological thorn in the side of those who favored emancipation, including Louisiana attorney David Patterson Dyer, who had studied law under Broadhead and worked in Henderson’s office.

Dyer had seen the brutality of human bondage in Missouri, including the sale of a black family when he was 12 and the public burning to death eight years later of a man who had killed his “master” in self-defense. His first court case was the unsuccessful defense of a man accused of enticing a slave to flee Missouri.

When the war began, Dyer joined the Union’s Pike County Home Guards and later was an officer in the 49th Missouri Volunteer Infantry. In 1862, he was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives, but still served as an assistant provost marshal in charge of military police in Pike County.

Monaghan received permission from the military to publish a newspaper and on May 14, 1863, the first edition of the Union appeared. It promised to editorially support “a vigorous prosecution of the War in suppressing the present rebellion and for the Union first, last and always.”

In his capacity as provost, Dyer immediately suspended publication and accused Monaghan of printing the Union on a press owned by disloyal residents. Monaghan replied by writing that Dyer had created an “irrepressible conflict” that would not end “until a provost marshal shall be found in the course of ultimate extinction.”

Dyer took the commentary as a threat, and had Monaghan arrested. The 2011 book “Lincoln and Citizens’ Rights in Civil War Missouri” by Dennis K. Boman says Monaghan was accused of trying to “break down the confidence of the people in those who are administering the Government and in the acts of the authorities to put down the rebellion.”

Monaghan spent almost three weeks in jail. The day after he got out, Dyer urged that the editor be sent back to Pennsylvania, writing that a “trip of this sort would do him good.” In another ironic twist, he apparently didn’t recommend sending his brother, Confederate soldier John S. Dyer, back to their native Virginia. In any event, Monaghan had a comeback.

“I am beginning to suspect that the scoundrelism that instigated this infamous proceeding against me and interrupted my private affairs is still at its assassin-like work,” he said.

Making his case

Though he had to again get permission from the military, Monaghan filed a civil suit against Dyer and provost colleague William Clinton Allison of Louisiana.

Monaghan charged them with false imprisonment and illegally stopping publication of the Union. Both sides lined up heavyweight witnesses.

Former state legislator and Union Col. George Washington Anderson of Louisiana called Monaghan a “pestiferous” traitor who was “using whatever ability and influence he possesses against the measure of the administration deemed most effective for the suppression of the rebellion.”

Among those backing the editor was Dr. Alexander Sharp, a brother-in-law of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

“The citizens of (Pike County) can imagine no other than personal motives to have influenced Mr. Dyer in his arrest,” Sharp wrote. “And considerable indignation is expressed at it.”

Missouri Gov. Hamilton Gamble said that if Monaghan were given an examination, the editor “could establish his innocence.” Not surprisingly, Dyer doesn’t mention the episode in his autobiography.

For his part, Monaghan would have done well to keep his mouth shut. Remarkably, he admitted he would have backed an insurrection to “forcefully” remove state lawmakers had they passed an emancipation law earlier in the year.

Monaghan also picked up his pen, writing to President Abraham Lincoln in November 1863 that he had been stifled because of opposition to Henderson’s bid for a full U.S. Senate term. Lincoln sent the letter to Gen. John Schofield, who had appointed Broadhead as Missouri’s provost marshal general.

Broadhead sided with Monaghan, saying the charges “seem to have been more personal than otherwise.” But by early 1864, Broadhead was no longer in his provost position and Schofield was replaced by Gen. William Rosecrans, who said he would not allow civil legal proceedings against officers or soldiers engaged in military duties.

Monaghan appealed to Gen. Odon Guitar, commander since July 1863 of the Union’s District of Northern Missouri. Guitar was a Kentucky-born lawyer and slaveholder who found that Monaghan was loyal and recommended the military stay out of the case.

Things might have worked out for Monaghan had Guitar not been reassigned in March 1864 after Union radicals “schemed for his removal,” according to the Missouri Historical Review.

The antagonistic, yet peaceful, conflict of words was about to turn violent.

The Kill List, Part 2

James Monaghan heard glass breaking and metal crashing.

The Weekly Union editor was walking in downtown Louisiana around 8 a.m. on the otherwise quiet Tuesday of May 24, 1864.

The Kill List, a secretive inventory of 52 Pike County residents targeted for murder because of their alleged Southern sympathies in the Civil War, had just been drawn up.

Because the document apparently has not survived, it isn’t clear if the newspaper writer was included. But he certainly opposed its lethal aim, and many on both sides would have loved to silence him and another local editor.

Monaghan strode from the street up the stairs to the Union’s second-floor office. He later described seeing six soldiers and a few townspeople ransacking the place. The editor demanded an explanation before ordering them to leave.

Just then, a shot rang out. The bullet missed its mark, but several men pounced on Monaghan and beat him before he was able to escape to a friend’s house.

“Presses were broken and thrown out of the windows, type was scattered on the streets and everything was destroyed within reach of the infuriated mob,” according to the 1883 book “The History of Pike County, Missouri” Damage was estimated at what today would be almost $17,000.

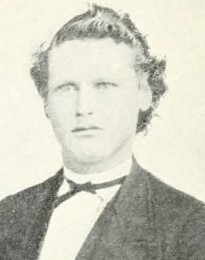

After a couple of hours, the firebrands took a break and went to the riverfront as the steamer Keokuk docked. Several agitators boarded the St. Louis-bound riverboat, but others remained on the wharf. They still had destruction in mind. This time, the target was the office of A.J. Reid, the brilliant but cantankerous editor of the Louisiana Journal.

Reid had been combative since taking over the paper in May 1859. Early in the war, he unabashedly supported the Union, but believed President Abraham Lincoln would be ineffective in healing the nation.

Reid’s caustic and provocative editorials could irritate pro-Union and pro-Confederate forces alike. Much to the chagrin of Southern supporters, he once suggested that a slave who escaped from a Pike County tobacco farm had made abolition “practical.” Another time, the target was peace-at-all-costs Unionists – called “Copperheads” – who were urged to “Crawl to your everlasting holes!”

Just three days before his office was attacked, Reid had offered harsh words for rebel sympathizers while equally criticizing those who sought “under the garb of Unionism to defy the law, to gratify personal hate and satiate the meanest passions.”

Though he avoided mentioning The Kill List directly, Reid’s words speak to its intent. He called such loyalty “spurious and detestable.”

“And if to denounce lawlessness calls upon our heads the opprobrium of giving comfort to and currying favor with the rebels, we shall only pity the man who so far misunderstands what loyalty is,” Reid charged.

The editor had been pilloried by Lincoln backers for his support of Union Gen. George McClellan in the presidential election that was a little more than five months away.

Reid said his loyalty was “of a higher type than that craven mercenary stuff which induces its possessors to endorse every wrong act” in the name of Union victory. He added that “too many men have appropriated the name of Unionism for base purposes” and were doing little more than trying “to gratify old grudges.”

The Journal missed its regular May 28 publication date, but thanks to “extra exertions” it hit the streets again on June 4. The only apology Reid offered was that he was not “in the most amiable frame of mind” when writing an editorial the day after the destruction.

In it, he put blame squarely upon radicals and said the paper would continue to decry disorder long after the “breeders of mischief” had been “buried in that deep pit of infamy, to which a virtuous and loyal people will justly consign them.”

In addition, Reid defended Monaghan by calling his competitor “a thorough Union man” and said “nothing disloyal has ever appeared in his paper.”

A quick response was issued by another Louisiana paper, the True Flag, which was edited by 25-year-old Union conservative Clay Crittenden Menefee Mayhall.

The rebels “will even have their apologists in the press of our county, as they have already had in times past,” Mayhall wrote. “The records of our county prove that one press in our city is owned either directly or indirectly, in whole or in part, by rebels of well-known dye.”

Journal readers caught up in the drama might have been forgiven for missing a Page 3 blurb in that June 4 edition. It was much more sinister.

The Kill List, Part 3

Meredith Jett was yanked off his horse and shot to death by men reportedly dressed as Union soldiers.

The 22-year-old Bowling Green farmer wasn’t wearing a military uniform and was of no threat to his attackers. Jett apparently was the first murder from The Kill List, a mysterious index of 52 Pike County residents targeted for death by radical Northern sympathizers for allegedly aiding the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Jett died the morning of Tuesday, May 31, 1864. His wife, Alice, was about six weeks pregnant with their first child.

Meredith was the son of Stephen Jett, who had moved with his family from Virginia to Kentucky as a teenager and then to Missouri after the passing of his first spouse. Stephen and Virginia native Patsy Parker were married in Pike County on April Fool’s Day 1834, and had five other children – Isaac, Joseph, Margaret, Washington and Franklin. The family lived in Cuivre Township.

Dates are unclear, but Meredith, Washington and Franklin served in Company D of Snider’s Battalion, a Confederate Missouri cavalry unit.

The June 4, 1864, edition of the Louisiana Journal said that though Meredith had been back home for at least a year, a motive for his murder may have been that he “was once in the rebel service.”

The killing likely was a response to ever-increasing raids by Confederate antagonists. That spring, unnamed rebels had been jailed at Bowling Green for being what one Union official called “the worst bushwhackers and thieves that Missouri has ever produced.” Local residents repelled an effort to break them out.

The biggest attack came 11 days before Jett’s murder, when up to 70 invaders crossed the Mississippi River at Louisiana to steal horses and ammunition. They returned to Illinois, but not before two men were wounded in a gun battle on the William Kindrick farm near Spencerburg.

“If the Union command gave little attention to guerillas in Pike County before, they reacted to this interstate raid with great concern and action,” noted Volume Three of the book series “Guerilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri” by Bruce Nichols.

There was little to go on in Jett’s death, but witnesses intriguingly claimed the soldiers responsible belonged to the 7th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, formed in 1861 by a blood-and-guts physician named Charles Rainsford “Doc” Jennison.

One of Jennison’s closest friends was familiar with Pike County. Union Col. James Montgomery, a former educator, minister and an avid abolitionist, had lived there from 1852 to 1853 before moving to Kansas.

Jennison and Montgomery – along with Union commander and former Congressman James Lane – were seen by some historians as perpetuating guerilla warfare that began along the Kansas-Missouri border and eventually spread.

Of course, Confederates and their ideologues shared blame for the violence, but early in the war soldiers of the 7th Kansas had unleashed predatory raids on Missouri residents, especially those with Southern allegiances.

The 7th had “just the right soldiers to root out the southerners in Pike County” who were “giving aid, support and intelligence to the bushwhackers,” Nichols wrote. A few of what the author called the 7th’s “hard cases” were waiting around St. Louis with nothing to do before their next duty in Memphis.

Their availability coincided with the mindset of the new Union commander in Pike County. Clinton Bowen Fisk ordered his troops to kill anyone with Confederate ties “wherever you find them in their hellish work.” The general was a deeply religious man from a military family who even so had a “take no prisoners” policy.

Fisk was another staunch abolitionist who loved shooting rebels, closing liquor joints and burning whorehouses. The New York State native said Missouri was full of “fiends” who were guilty of “villainy and corruption.”

Three days before Jett’s murder, Fisk had ordered 50 men sent to Pike County from Palmyra “on a mission of extermination.” There’s no documented evidence he played an active part with The Kill List, but it would be highly surprising if he did not at least have knowledge of it.

On the day Jett died, the general inquired about sending even more soldiers to “wage a war of sure and swift destruction against the murdering, thieving gang of villains that are now at work in Pike and neighboring counties.”

Unidentified members of the 7th Kansas were told not to ask questions as they were sent to Pike County, and there’s no surviving proof of what they did once there. Nichols submitted that what happened over the next week – which covered the date Jett was shot – was “not entered into the war record” of the regiment.

Jett’s killers were not brought to justice. His widow gave birth to a girl, Meredith Cornelia “Nellie” Jett, in Bowling Green on Jan. 20, 1865. That same year, Alice Jett married her late husband’s older brother, Joseph. They would have five more children. Washington and Franklin Jett survived the war.

Though Meredith Jett was out of the way, one famous Pike County rebel – a likely entry on The Kill List – would elude capture for the rest of the war.

The Kill List, Part 4

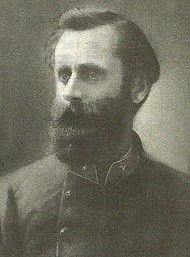

It would be surprising if Caleb Dorsey wasn’t on The Kill List, the Civil War register of Pike County residents targeted for death due to their Confederate support.

He was one of the reasons the Union funneled more troops into the area during the spring and summer of 1864. The 30-year-old Louisiana farmer quietly was recruiting dozens of his neighbors for the rebel cause.

Advertising was unnecessary. While the same could likely be said of Northern sympathizers, many Pike County residents who supported the South had grown tired of living in fear of reprisals.

Dorsey mostly remained low-key, but certainly knew how to make a splash when he wanted. A newspaper reported he once showed up for Sunday services at Buffalo Knob Church near Louisiana in full Confederate uniform. A colleague, Maj. John N. Edwards, described the colorful commander as “among the most soldierly and dashing” of the rebel officers.

The fourth of 11 children, Dorsey was from a prestigious family that had arrived in Virginia in the 1650s and later moved to Maryland. Dorsey was a year old when his parents, Edward and Eleanor, came to Pike County. Before the war, he was a sergeant in a Union cavalry company.

After the death of his father in 1858, Dorsey maintained the family’s land holdings worth what would today be more than $700,000. Upon the outbreak of hostilities, he sold inheritance rights to an older brother for the 2021 equivalent of almost $86,000 to become an officer with a Confederate cavalry unit. He also commanded a rebel infantry brigade.

Family conversations during the war likely were tense. Dorsey’s mother and several siblings held Confederate sympathies. However, his sister, Mary, was the wife of James Broadhead, a high-ranking Union officer and one-time Bowling Green attorney. Another sister, Comfort, was married to former Congressman and Union-supporting Judge Gilchrist Porter.

Proof that they spoke at least occasionally came after Caleb was captured by Union forces near the Osage River on Feb. 15, 1862.

Broadhead requested parole, claiming his brother-in-law would make amends once he returned to Pike County. Caleb was released from a Massachusetts military cell in a prisoner exchange on Aug. 27, 1862, and rejoined Confederate comrades the day he got back to Missouri.

“Those good family influences that Broadhead alluded to included a mother and three sisters who were devoting all of their time to sewing Confederate uniforms and assisting the Confederate soldiers in Pike County,” wrote author Lynne Roberts.

Dorsey popped up across Missouri and in Arkansas over the next two years, but avoided recapture even when returning home. In 1864, he was rounding up troops for a last big push planned by Confederate general and former governor Sterling Price.

Dorsey’s inclusion on The Kill List would have made sense, because he was “one of the most successful behind-the-Union-lines Confederate recruiters throughout the Civil War in Northeast Missouri,” wrote Bruce Nichols in “Guerilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri.”

The under-the-radar approach infuriated Gen. Clinton Fisk, who commanded the Union’s District of Northern Missouri. He was more determined than ever to catch the “ghost rider.” In part because of Dorsey’s efforts, Fisk wrote on July 1, 1864, that “serious troubles exist in Pike County.”

The original Kill List, supposedly featured 52 names, has been lost, but the first victim was former Confederate soldier Meredith Jett, who was shot to death on May 31, 1864 – allegedly at the hands of soldiers belonging to the Union’s 7th Kansas Cavalry.

The next week, the Louisiana Journal reported a man named Murphy was killed near Ashley. Available records do not list a first name or provide more details, but soldiers of the 7th again were blamed. The Union-supporting paper said Murphy was “a peaceable citizen” whose only offense was that he would not let the soldiers to take his horse.

“Well, may we inquire in what country do we live in, and to what state of society are we drifting?” the paper indignantly asked.

Even if Murphy was not on The Kill List, dozens of other Pike County men certainly would have qualified, including:

*John Quincy Burbridge, 34, a Louisiana banker and Confederate colonel who once urged his troops that instead of killing enemy soldiers outright, they should aim for the waist because such a wound “nearly always gives the victim time to prepare to meet his Maker.”

*Burbridge’s 30-year-old brother, Clinton Dewitt Burbridge, who was awaiting a second trial on spying charges after the first was called off due to a technicality. He and John recruited hundreds of men to the rebel cause.

*Eighteen-year-old Samuel Minor, a member of Dorsey’s regiment whose youthful looks twice helped him avoid capture – once by posing as a 10-year-old boy and another time by claiming he was an agriculture student at the University of Missouri.

*Cavalry Lt. Thomas Dalton, 32, of Bowling Green, a New Hampshire native who was orphaned at seven and grew up on an uncle’s Ohio farm later owned by President James Garfield. “Though he was a New Englander by birth, he was a Missourian by adoption and at the opening of the war joined the ranks of the confederacy,” the Bowling Green Times noted.

*Retired Capt. Archer Bankhead, 30, a livestock dealer and direct descendent of President Thomas Jefferson, who lived at what is now Eolia.

*Eighteen-year-old Champ Shaw, a private from the Eolia area who was one of Price’s bodyguards.

But of all The Kill List’s potential victims, one person may have stood out simply because a different pronoun had to be used.

The Kill List, Part 5

Since written evidence likely does not exist, it’s presumed that all of the names on The Kill List were male.

The Civil War inventory featured 52 Pike County Confederate sympathizers marked for murder by Union radicals. And while chivalry probably prevented it, there certainly were women candidates to consider.

In an ironic twist so common during the war, the most likely female possibility also could be called the most improbable.

Mary Frances “Fannie” McQuie Senteny was the daughter of a highly successful Louisiana business owner, a seminary student, a wife and a mother.

But by the time The Kill List was penned in 1864, she had lost her husband at Vicksburg and was a suspected Confederate spy.

One Union backer who knew Fannie well was Louisiana businessman Edwin Draper. He and his brothers, Philander and Daniel, were partners in mercantile, livestock, lumber and real estate businesses.

Just three months before federal troops began to turn the tide of the war with a victory at Gettysburg, Draper confided his frustrations with Confederate bushwhacking in Pike County.

“While humanity is certainly commendable in some cases, it is a question how far these courtesies ought to be extended to the most inveterate rebels, male and female, in the rebel army, who have been protected here in the enjoyment of all the rights and privileges due to loyal citizens, and they have repaid it by constant abuse of Union citizens,” Draper wrote on April 1, 1863.

Fannie was born in Louisiana on Sept. 27, 1840. Her parents were Southerners. Edward Goode McQuie was from Kentucky and arrived in Pike County just before his 20 birthday in May 1824 He married Virginia native Elizabeth H. Yale on Feb. 25, 1835.

For a while, the McQuies and Drapers attended church together and were members of the same Louisiana civic organizations.

Records show that from 1855 to 1857, Fannie was a student at Monticello Seminary in Godfrey, Ill. Its founder, War of 1812 Navy veteran Benjamin Godfrey, was a proponent of higher education for women – a rarity at the time – and hoped the seminary would lead to “the moral, intellectual and domestic improvement of females.”

On her 18th birthday, Fannie married another Louisiana native, store owner Pembroke S. Senteny. The ceremony took place in the McQuie’s just-completed Greek Revival home on North Third Street, which still stands.

When the war broke out, Senteny became an officer with the 2nd Missouri Confederate Infantry. He was “a brave soldier and an accomplished gentleman” whose men “loved him as their friend, and honored and esteemed him as their commander,” according to an 1868 memoir by Ephraim McDowell Anderson.

Missing her husband as the fighting dragged on, Fannie began the dangerous practice of crossing Union lines. In his April 1863 letter, Draper says she and other relatives of Pike County Confederates had “kept up a constant communication with their friends in the rebel army” and that “by these means they greatly aid and comfort” the enemy.

While admitting he didn’t believe the actions of Confederate sympathizers were an immediate threat, Draper said such traitors should be given “nothing but the most degrading and brutal treatment.”

In addition to the McQuies aligning with the South and the Drapers favoring the North, a split between pro-federal and pro-secession members of Louisiana’s Methodist Episcopal Church led to a legal battle over sanctuary ownership.

Judge Gilchrist Porter, a Union supporter who had Pike County in-laws that fought for or backed the South, ruled for the pro-Northerners. The case was appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, which sided with Southern loyalists.

Fannie relayed letters, supplies and other items from Louisiana to Confederates. The practice upset Union commanders and there was evidence that Fannie met with Confederate leaders, but treason allegations were never proven.

However, Pembroke Senteny paid the ultimate price. It happened at the hands of a Union sniper during the Siege of Vicksburg on July 1, 1863.

“About dark, (Senteny) was looking over the works and making some observations when he was shot through the head by a minie ball and killed instantly,” Anderson wrote.

“With bitter tears of grief and sorrow the regiment beheld the body of this gallant officer, who led them through many trying scenes and fiery ordeals, now borne back a corpse,” the author continued. “No more would we hear his calm and deliberate, though firm and quiet, commands, and be reassured and stimulated, in the hour of danger, by his self-possessed and determined bearing.”

It is unclear if Fannie continued spying after her husband’s death. In 1873, she married a widowed attorney from Palmyra named Thomas Lilbourne Anderson Jr., the son of a former state lawmaker and secessionist U.S. Congressman.

Other Pike County women who drew the wrath of Union supporters included:

*Lydia Laurie Carr, a poet who was arrested for spying and sent for resettlement in the South.

*Alice Block, a Confederate whose Union-sympathizing husband, Henry, was administrator of the Aberdeen plantation.

*Louisa Meriwether, a smuggler who provided the rebels with supplies.

In addition to her two children by Pembroke Senteny, Fannie would have two more by Anderson. Fannie died at her family’s Louisiana home at 87 on Sept. 7, 1928. She is buried in Riverview Cemetery.

In 1920, a memorial plaque honoring Pembroke Senteny was placed among others at the Vicksburg National Military Park.

The Kill List, Part 6

Harassment of those who supported the South during the Civil War did not stop with The Kill List.

Radical Unionists in Pike County were responsible for scrawling out the names of 52 people targeted for murder in 1864. Their colleagues statewide created a much less violent method of repression after the Confederate surrender a year later. Many would argue elements of the approach are alive today.

At least two men thought to have been on The Kill List were murdered – Meredith Jett of Bowling Green and a man identified only as “Murphy” from Ashley, but as many as eight may have died.

No one was brought to justice, which emboldened those bent on vengeance. Even some who had not taken sides in the war were ensnared.

One of them was Father John Cummings, who was arrested after saying Mass at St. Joseph Catholic Church in Louisiana on Sept. 3, 1865.

His crime? Failing to recite the “loyalty oath” outlined in the Missouri Constitution updated by legislators and narrowly approved by voters earlier in the year.

The oath required people across many professions to proclaim their allegiance to the United States and the Missouri Constitution, and did not allow them to work or vote if they’d ever been disloyal.

Similar pledges had been around at least since the founding of the country. The Constitution itself requires the president and other officials to take an oath, and most have consistently been upheld as legal. But the 1865 Missouri effort was different because it sought to punish individual belief and past acts.

Its 194 words contained 86 acts of alleged “disloyalty.” Those who refused to take it faced a $500 fine — the equivalent today of more than $7,500 – and six months in jail. Religious leaders were among the first to object.

“I believed it to be wicked thus to surrender the claims of Christ to the demands of Caesar, and resolved, at the hazard of fines and imprisonments, yea, even of life itself, that I would refuse compliance with this unrighteous requirement,” declared the Rev. Barry Hill Spencer.

Cummings’ detractors were just as adamant. The Bethany Times newspaper said the “hottest corner of hell (was) awaiting such preachers.”

Cummings was locked up with men accused of horse theft, burglary and rape. A grand jury in Bowling Green – made up of men who had recited the oath – indicted him on Sept. 4, 1865.

“Cummings’ resistance to ideological thought control made him something of an instant celebrity,” said The Rev. Donald Rau in “Three Cheers for Father Cummings,” published in “The Journal of Supreme Court History.”

At a court appearance on Sept. 8, a defiant Cummings refused to enter a plea and stood just long enough to recite the Apostles’ Creed, a reaffirmation of faith in the divinity of God and Jesus Christ.

Cummings refused bail and was set for trial before Circuit Judge Thomas James Clark Fagg of Louisiana, another oath-taker. The priest confessed his guilt, but criticized the law as a violation of religious freedom.

Fagg found Cummings guilty and fined him the state-mandated $500. Ironically, the decision was handed down in the Methodist Church at Bowling Green, which housed legal proceedings after fire had destroyed the county courthouse in 1864. The priest refused to pay, and would not let anyone else fork it over. So, Fagg sent him back to jail.

“If Father Cummings wished to generate publicity for the plight of clergymen in Missouri under the new Constitution, he succeeded admirably,” Rau noted.

Cummings appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, which upheld Fagg’s ruling. The Archdiocese of St. Louis helped bankroll an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard arguments on March 15, 1866.

The case “engaged the attention of the ablest lawyers and jurists” and “the deepest interest was felt throughout the whole country,” wrote William Leftwich in “Martyrdom in Missouri.”

A ruling came on Jan. 14, 1867. The high court sided with Cummings in a 5 to 4 vote, with Chief Justice Salmon Chase among those saying the Missouri oath should be upheld.

Writing for the majority, Justice Stephen Field said the oath was of “objectionable character” and tended to “subvert the presumption of innocence.” Such required vows “assume that the parties are guilty; they call upon the parties to establish their innocence; and they declare that such innocence can be shown only in one way – by an inquisition, in the form of an expurgatory oath, into the consciences of the parties.”

Cummings and other clergy who had been arrested were now free to minister again. However, that was hardly the end of matters.

The Missouri Supreme Court “reluctantly accepted” the higher court’s ruling, but “drew a distinction between voting and the practice of a profession,” wrote Joseph A. Ranney for “In the Wake of Slavery: Civil War, Civil Rights and the Reconstruction of Southern Law.”

It took state lawmakers until 1871 to repeal the loyalty declaration. Four years later, a new constitution was adopted without it. Father Cummings served at St. Stephen’s parish near Monroe City before falling ill. He died at age 33 on June 11, 1873, and is buried in St. Louis.

The Supreme Court would deal with many more cases addressing loyalty oaths over the next century, often siding with the rights of the people over desires of government. Vows that included swearing allegiance to the United States generally passed muster. Those that circumvented the right to free association or required submission in exchange for benefits were thrown out.

However, at least 15 states still have some form of loyalty oath, and at one time during the Cold War of the 20th century as many as 42 did. Arguments are still being made about the role of government in regulating speech.

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black called the Cummings case “one more of the Constitution’s great guarantees of liberty.” Writing in the Missouri Historical Review, author Harold C. Bradley hoped history would remember the priest.

“If it is unfortunate that we have forgotten the lesson of a case important in the history of our freedom, it is foolhardy for us to ignore the man responsible for the case and allow his story to fade from our consciousness,” he said in 1962.

One Baptist elder went beyond the politics. The Rev. James Duval had also been jailed in 1865 for not taking the oath. He reasoned that the law could temporarily place people in shackles, but it would never imprison the Word of God.

“After the decision in the Cummings case, we were all discharged from custody, and are still engaged in trying to preach Christ – the Way, the Truth, the Life – to sinners,” Duval triumphantly declared.

Editor’s note: Story by award-winning print and broadcast journalist, historian and public relations professional Brent Engel of Louisiana.