PIKE COUNTY, Mo. — The man for whom the Pike County town of Ashley is named made a bold request almost two centuries ago this month.

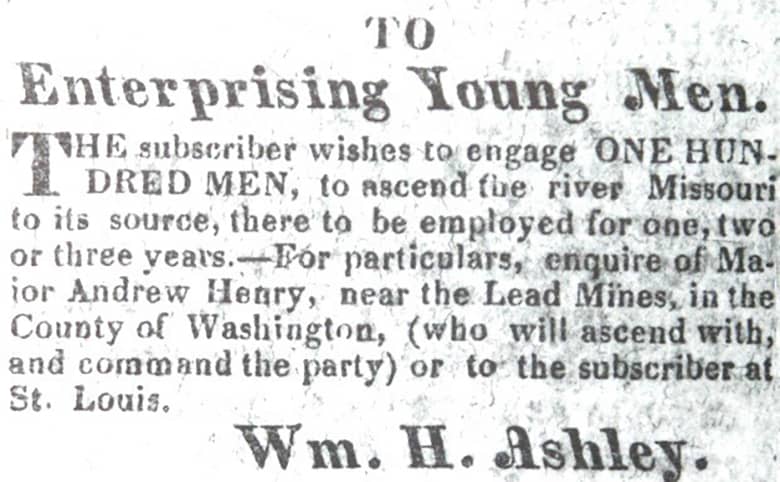

It appeared in the St. Louis Gazette and Public Advertiser on Feb. 13, 1822, and was addressed to “Enterprising Young Men.”

William Henry Ashley, a business entrepreneur and the lieutenant governor of Missouri, was looking for rugged souls who were willing to traverse the Missouri River and spend up to three years working the fur trade.

The catch was that trappers would largely be on their own in what was still an untamed, isolated and dangerous land.

At the time, the fur business mostly involved large companies from faraway places sending agents to deal with Indian tribes. Ashley and business partner Andrew Henry proposed cutting out the middle man by having trappers fan out and bring to a central location as many pelts as they could carry.

“This innovation in the fur trade was destined to have a far-reaching effect on the development of the west,” the Sheridan Post newspaper would later write.

Henry set out from St. Louis in April 1822 and within four months had traveled almost 700 miles to the mouth of the Yellowstone River in Wyoming, where he built a fort. Ashley left St. Louis in May 1822, but had to turn back when a keelboat overturned. After getting fresh supplies, he met Henry.

An Indian attack that led to the deaths of 15 men from Ashley’s party and financial troubles resulting from a lackluster harvest of animal hides forced a return to St. Louis in spring 1823.

“Few individuals can be said to have exercised a greater influence on the course of the fur trade of the Far West,” wrote historian Harvey L. Carter. “His advertisements attracted some of the ablest younger men to the business and his own success was a pattern for them to emulate.”

Author Philip F. Anschutz said that in just four years, Ashley “rewrote the several-centuries-old playbook for gathering furs from Indians across the North American continent by transforming his industry’s business structure.”

“Ashley surpassed all his rivals as a brilliant frontier entrepreneur,” added author William R. Nester. “Through ceaseless, fearless and often ruthless enterprise, he rose from obscure, humble origins into enormous wealth and status.”

Ashley dissolved his partnership with Henry, and sent some of his ablest men to explore the Green River Valley of Wyoming. It would be one of his best decisions.

Late bloomer

Unlike many of the people he would inspire, Ashley didn’t charge into the wilderness.

He was born in Virginia in 1778. Few records survive about what historians have said was an unremarkable family, but Ashley was smart and determined.

“Although possessing only a rudimentary formal education, Ashley learned to express himself well in written English, which he combined to advantage with his natural talents in math and bookkeeping, surveying, map making and geology, riding and shooting — all useful skills for his profession, even if they lacked the polish necessary to join the ranks of Virginia’s landed elite,” Anschutz wrote.

After failing at farming in Kentucky, Ashley moved to Missouri at age 24 and settled in Ste. Genevieve. He initially found success in lead and saltpeter mines and improved his fortunes when he got into gunpowder sales and real estate speculation following marriage to Mary Able, the daughter of a man who held Spanish land grants.

Also proving valuable would be organizational skills learned while serving as a brigadier general in the Missouri Territorial Militia during the War of 1812. Ashley was described as five feet nine inches tall with a slender build, a hooked nose and a firm chin.

“Socially awkward, stiff, reserved, distant, graceless and self-disciplined, he developed few close relationships, even among lifelong friends,” Anschutz said. “Such characteristics may have hindered him socially, but this same formality made Ashley a natural leader of men.”

Dr. Frances L. McCurdy, an associate professor at the University of Missouri, would offer a different view of Ashley’s appearance.

“A picturesque and dashing gentleman, he epitomized the ideal of the western man, and the announcement of his expected presence at a gathering would bring many a man there to shake his hand,” McCurdy wrote.

In 1819, Ashley moved to St. Louis and a year later was chosen as Missouri’s first lieutenant governor. It was during the term that he would be thrust into prominence.

“The office was not a demanding one and Ashley formed a partnership with his old friend, Andrew Henry, to engage in the fur trade of the Rocky Mountains, in which Henry had already had considerable experience,” Carter noted.

Mary Ashley died on Nov. 7, 1831, but her husband’s grief was soon remedied by the prospect of exploring the Rockies.

The promised land

Ashley and his party set out in November 1824, not long after he was defeated for Missouri governor by Frederick Bates.

“The journey was plagued by brutal cold, slicing winds, a scarcity of firewood and snows so deep that at times the only way the men could advance was to follow the paths made by wandering buffalo herds,” said author Eric Jay Dolin.

The explorers might have died had it not been for help from the Pawnee, who provided advice and replaced the white men’s dead horses.

Ashley’s caravan men reached the Green Valley on April 19, 1825. Three days later, he split the men into four parties, all of which were to go into the mountains and trap beaver. They then were to reassemble in three months at a river location chosen by Ashley, who left markers for the trappers to follow.

An estimated 120 men had arrived by July 1 at the rendezvous point near what is now a bump in the road called Burntfork in Southwest Wyoming. In addition to Ashley’s contingent, there were mountaineers employed by the British-owned Hudson Bay Company and Native Americans.

The men, and the women and children who accompanied them, were “assembled in two camps near each other about 20 miles distant from the place appointed by me as a general rendezvous,” Ashley recalled in his diary. They had been “scattered over the territory west of the mountains in small detachments.”

The “only injury we had sustained by Indian depradations (sic) was the stealing of 17 horses by the Crows…and the loss of one man killed on the headwaters of the Rio Colorado by a party of Indians unknown,” he recalled.

James Pierson Beckwourth, a man of mixed race who was born a slave in Virginia and whose name still is attached to a Sierra Nevada mountain range pass, described the scene.

Ashley “would open none of his goods, except tobacco, until all had arrived, as he wished to make an equal distribution,” Beckwourth wrote, adding the obvious in saying that provisions were scarce in the mountains.

“When all had come in, (Ashley) opened his goods, and there was a general jubilee among all at the rendezvous,” he continued. “We constituted quite a little town, numbering at least eight hundred souls, of whom one half were women and children. There were some among us who had not seen any groceries…for several months. The whisky went off as freely as water, even at the exorbitant price he sold it for. All kinds of sports were indulged in with a heartiness that would astonish more civilized societies.”

Ashley said the gathering lasted one day. Others claimed it was a week. Ashley’s recollection may be clouded by the fact that he left the next day for St. Louis with almost 9,000 beaver pelts. No matter who is right, it is considered the first large-scale meeting of what would be annual reunions over the next 15 years.

“The rendezvous system, where trappers remained in the mountains year-round, meeting an annual suppliers’ caravan at what amounted to a mobile trade fair, revolutionized the fur business,” Anschutz wrote. “The rendezvous removed the need for expensive fortified posts in the mountains, provided trappers with ready access to supplies and usually kept them in debt to their suppliers.”

Another calling

There’s no doubt Ashley enjoyed being a trendsetter, but another passion would soon demand its due.

“His life indicates that he desired prominence in public affairs, and that his business activities were but a means of acquiring a competence sufficient to enable him to gratify this ambition,” wrote author Donald McKay Frost.

The political bug had bitten Ashley when he was Missouri lieutenant governor. The itch remained even after he was defeated for the top job by Bates, who would become known for vetoing a measure to outlaw dueling.

The decision would benefit Ashley. Just after the rendezvous in July 1826, the general sold his company for what would now be $400,000 to three men he had worked with and knew well — Jedediah Strong Smith, William Sublette and David Jackson, all of whom made their mark in western exploration. In four years of fur trading in the Rockies, Ashley estimated his company made $200,000 — or $5 million in today’s dollars. Ashley agreed to continue supplying goods to the rendezvous, but his focus was clearly on politics.

“Ashley apparently quit the mountains without regret,” wrote historian LeRoy R. Hafen. “He never was a Mountain Man at heart; his interests were with politics and business in Missouri. With a fortune in hand, he would give up the hazards of trapping and take over the surer business of supplying the trappers and marketing their furs.”

The opportunity for political office came again in 1831. The race between incumbent Congressman Spencer Pettis and challenger Thomas Biddle was so volatile that the two men dueled on Aug. 27. Both were so badly injured that they died within two days.

Gov. John Miller called a special election for Oct. 31. Pettis had been a strong supporter of Democrat President Andrew Jackson. Biddle had argued for issues touted by Henry Clay, a former presidential candidate and later a founder of the Republican Party. Ashley was seen as a man who “would afford harmony and satisfaction to the entire population of the state” and whose “popularity could not be denied,” historian James Earl Moss wrote.

“As a prime mover in the growth of Missouri from territorial wilderness to statehood, Ashley had been instrumental in developing commerce and industry, and his activities proved him a man of education as well as ability,” Moss added.

Ashley formally threw in his hat on Sept. 20 — just six weeks before voters were to cast ballots. He backed many of Jackson’s policies, but broke from the President on several key issues. Above all, he pledged to represent the people before party. It was far from an empty promise.

“A public servant should have no concealed opinions touching the interest of his constituency,” he wrote.

On Oct. 3, Democrats from 20 Missouri counties met to discuss whether to support Ashley or St. Charles attorney Robert William Wells. The group chose Wells. That changed when Missouri U.S. Sen. Alexander Buckner announced his support for Ashley. The general won the election by just 120 votes out of 9,740 cast.

“His popularity and political cleverness put him above political parties or factions as he drew votes from all elements of the population,” Moss said.

Ashley was re-elected in 1832 and 1834. Not surprisingly, he voted independently and remained a staunch supporter of development in the West.

“Although he was never a major force in Congress, Ashley remained popular with Missouri voters because he successfully looked after the state’s interests,” according to “Dictionary of Missouri Biography.”

Ashley declined to seek re-election in 1836 and ran unsuccessfully that year against Lilburn Boggs for governor. After the defeat, he continued working in real estate. The general had two other wives. In 1825, he married Eliza Christy, but she died in 1830. He walked down the aisle for the final time with Elizabeth Woodson Moss on Oct. 17, 1832.

The couple later moved from St. Louis to a farm in Cooper County west of Boonville, where he died of pneumonia at age 60 on March 26, 1838.

Ashley had ordered that he be buried in an Indian mound atop a bluff on the property overlooking the Missouri and Lamine rivers. The grave’s location remained a mystery for years until Judge Roy T. Williams of Kansas City led an effort to have a marker placed in the late 1920s.

There is no known authenticated photograph of Ashley, although several modern websites offer a picture of another man that probably was taken later in the 1800s.

“Ashley’s place in history is that of a man of energy and action, to whom the making of decisions came easily and naturally,” Hafen wrote.

One more thing

After Ashley died, third wife Elizabeth married again.

Her beau was U.S. Attorney General John Jordan Crittenden, who served three Presidents. It was also his third time at the altar. Though she never held office, Elizabeth certainly knew how to speak like a politician.

“Tradition has it that when Elizabeth was asked by her sister which (husband) she found the most satisfactory, she answered that her life would have been incomplete without all three,” according to the October 1952 edition of the Missouri Historical Review.

A copy of the newspaper ad William Ashley took out on Feb. 13, 1822.